January 19, 2015

by TheCuriousCyclist

Filed under Advice

Tagged with newzealand

Should I cycle the North island or the South island?

If you’re on a bike, you’ll probably have to decide between one or the other just for the sake of time. It’s possible to ride onto a ferryboat between Wellington and Havelock, but there is honestly so much to see on either island that you’ll feel rushed trying to see both, unless you have a month of travel time at least.

Here’s the short summary: If you prefer grand snow-capped mountain vistas, icy fjords, and camping, you’ll like the South island more. If you prefer snorkeling and diving, rolling farmland, and geothermal attractions, you’ll like the North island more. Both have plenty of hiking, kayaking, river-rafting, swimming, camping, boating, mountain-biking, museums, farm-stays, nature preserves, etc. An excellent resource is the NZ Frenzy Guidebook.

You may plan a trip of a couple hundred miles and end up ditching it in favor of the nine different things you can do right around your starting point!

What are the best times of year to cycle in NZ?

Summer and fall, between November and March (since NZ is in the southern hemisphere) are best, as you might expect. The tourist rush is heaviest in January and February, so you’ll want to book the most popular attractions and hotels a month or two in advance.

What sort of weather should I anticipate?

The North island is comparable to coastal California, including occasional rain. You’ll want to pack some clothing that can be layered, and include some rain gear. Chances are it will rain at least once every week of your trip.

The Southern island is a bit colder and windier – increasingly so as you travel South on it. This might become a danger on busy roads. If you’re camping you’ll need tent stakes.

What sort of terrain should I anticipate?

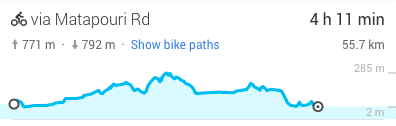

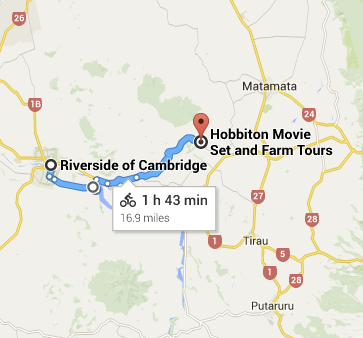

New Zealand is mostly hills. Not huge bust-your-neck-vein hills, but gently rolling hills, one after the other. You won’t escape these hills unless you’re traveling right on the coast, and even then there will be hills much of the time. Make sure your bike has a “granny gear”, and plan each day’s distance as though you were traveling it at about 4mph.

On the other hand, you’ll be out in sunshine and very fresh air, traveling almost entirely through rural countryside.

The “mountain bike” is king in NZ, and you’ll find tracks and trails that are suitable for mountain biking all over the place. If you can find a place to stow your long-range gear, you might want to try stripping your bike down for a day and zipping around on a few trails.

What sort of roads and traffic should I anticipate?

The most important thing to know: People drive on the left in NZ, and therefore you cycle on the left. If you’re from California it may take you a few days to reverse all your instincts.

The second-most important thing: Native New Zealanders drive fast – much faster than they should – even on winding roads full of blind curves and rapid (for drivers) elevation change. When you’re out in the countryside, keep an ear open so you can move well to the side when you hear a driver coming. If you’re on a highway, stay as far left as you possibly can. Get some bright clothing, or a safety vest or a flag. That all-black “pro” outdoor gear is great against weather, but not great for visibility!

Also, get yourself a rearview mirror. If you look into it and see an upcoming car, and there’s also an oncoming car such that they’ll be passing each other right as they pass you, you should probably get off the road entirely until they pass, even if it means going into the bushes.

This rule especially applies for trucks. The drivers are sometimes unaware of their size, and unaware that their tailwind can knock a cyclist down – or possibly right into other traffic!

Avoid Highway 1 in the far north as much as you possibly can.

The pressure to avoid fast NZ drivers will hopefully encourage you to seek out less-traveled country roads – where the true glory of cycling in NZ can manifest. You’ll need some good-sized tires (not the narrow urban ones) because many of these roads are hard-packed dirt and gravel, or only roughly paved.

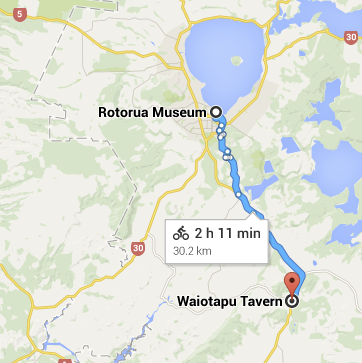

If you have a laptop, a tablet, or even a phone, it’s a good idea to look over your next day’s route at the highest resolution in Google Earth – or even better – with “street view” on Google Maps. You can often figure out what kind of roads you’ll be covering before you even go near them.

Can I bring my bicycle over on the plane?

Yes. If you’re going to NZ, it’s most likely that you’re flying via Air New Zealand, and their policy is pretty good for bicyclists. They have an oversize baggage exception for sporting equipment, which includes bicycles that have been properly packed for transport. When you buy your ticket you can save money by buying “extra bag” units up front. You’ll need at least one for your bicycle.

Note that their regulations have a strict 70-pound limit for any one box, sporting equipment or otherwise, and that includes the weight of the box itself. The good news is, if you pack up your bike and end up splitting it into multiple containers to pass the per-container size or weight requirement, Air NZ will actually count the containers as one item!

If you fly by some other airline – even partially – then you need to respect their rules for luggage, which may be different, and are probably more expensive. Factor that in when you’re looking at ticket prices. Check the Air New Zealand website directly, instead of just using Priceline or Kayak, because they sometimes have special ticket sales that can save you quite a lot of money.

What about a recumbent bicycle on the plane?

If you’re bringing a recumbent, you’ll probably need to use a box that goes into the oversize category, to contain the boom – the spine of your recumbent – for shipping. For example, the Crateworks Tandem box is 70 x 11 x 32 inches, which puts it in the oversize category. You’ll need two “extra bag” units for that box – one because it’s an extra bag, and one because it’s in the oversize category even for sporting equipment. Contact your departing airport in advance, and tell them what you’re bringing and when, if you’re especially paranoid.

On the way out of New Plymouth airport I had a disagreement with an Air NZ employee who claimed that it was not actually possible to pay for the “oversize” status in advance, even though the charge was the same as for an “extra bag”. She said that even though I’d purchased eight extra bag units to more-than-cover my three oversize boxes (two recumbents), I needed to pay three “oversize” charges on top of that anyway before they would load my gear.

I calmly pointed out that the company website says, quite clearly, that the oversize charge is “same as first excess bag charge”, and that there is no sign of a separate “oversize” charge, nor any place to specify one when purchasing tickets. She claimed that it didn’t matter, and I still needed to pay.

When I asked her if we could just redeem the cost of the unused “extra bag” units – five in total – and use that money to pay the three “oversize” units, she said no, because it would take more time processing the refund than we had before the flight. I said “okay” and asked if we could redeem our unused “extra bag” units after the flight instead. She said no – after the flight, it would be too late.

“Okay, how do I redeem them now?” I said. She told us to leave the line and go to a courtesy phone and call up a service department. I asked, “what are the chances we’ll get that done before we have to board the plane?” She said, “not very good, actually.”

So we started over again – quoting from Air NZ’s own website, patiently explaining how SFO had handled it, and generally making our case in a civil manner. Somewhere along the way she realized that, on the face of it, she was deliberately screwing two customers out of 500 dollars for no good reason. She left the desk and talked to the department manager, who took one look at the line behind us, and said, “just send them through.”

The moral of the story is: Sometimes the sheer size of a packed bicycle will cause airport staff to doubt the policies of their own airline. They are used to telling people “no”, and used to people bending the rules. Don’t get upset – remember that in this sort of encounter, the first party to get upset usually loses.

Make your case, and back up your claims with their own documentation. Show them their own website on your phone so they can read it themselves. Yes, one bicycle packed up into multiple oversize boxes really is equivalent to one oversize item, which really is is the equivalent of two “extra bag” purchases on the website. Show it to them, then show it to their manager, then show it to their manager’s manager.

How do I get my bicycle to/from the airport?

You’ll want to box up your bicycle well before the departure date, to make sure you pass the weight requirements. You’re very unlikely to find a box at the airport, let alone have time to pack it properly. That puts a few other things on your to-do list:

You’ll need to arrange transport to and from the airport, for yourself and a large box. You’ll also need to arrange for a safe place to store your box while you’re in NZ, so you can use it for the return flight, or if you’re leaving from a different city, you’ll need to ship the box between your starting and ending city. This sounds harder than it really is – you can set it up just by sending a few emails.

Air New Zealand can fly you in or out from a good number of cities, connecting with Auckland, where all international flights arrive and depart. All these airports have hotels nearby, and many of those hotels will offer to store your folded-up box somewhere while you go on your trip.

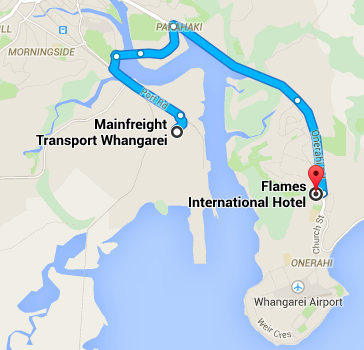

If your trip ends in some other city, it’s very likely you can find a hotel that will hold a shipped package for you. So, when you arrive in NZ, you can fold up your box, tape it thoroughly closed, and ship it across the country. It will be too big for the regular NZ post office to handle it, but the official alternative – Mainfreight – will do the job. For an extra fee they offer a package pickup service, but there’s a good chance you can use a taxi service or a shuttle from the airport or hotel to deliver your box to the nearest depot, just before you set out. Shipping times are usually only a couple of days, so your box will arrive way ahead of you!

Are there alternate modes of transportation that will carry me and my bike?

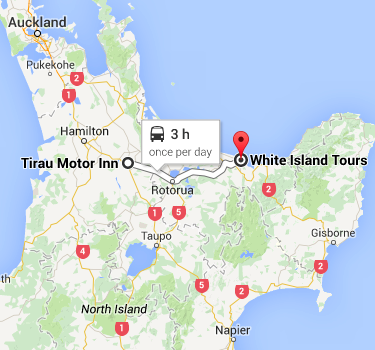

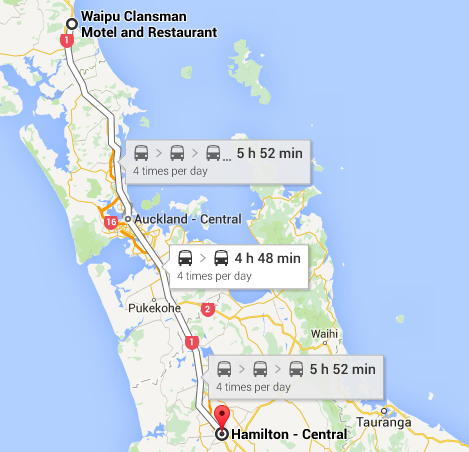

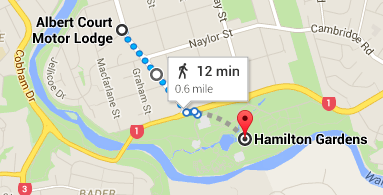

NZ has a very good shuttle system between all the major cities and most of the minor ones. You can purchase tickets in advance, and all the routes will carry your bicycle, with a few exceptions.

After booking your route, it’s a good idea to inform the driver that you’ll be traveling with a bicycle by calling or emailing a day or two in advance.

The ferry between the North and South islands will accept bicycles – just roll them over to the luggage area they designate. Then move all your most valuable items to your backpack, and carry that with you for the ride.

There is a train line on the North island based in Auckland that is faster than the shuttles along the same route, but their bicycle carrying policies are more restrictive.

If you really want independence you could rent a minivan and toss your bike in the back, but this will cost you a lot of money in NZ relative to California, especially if you plan to return the vehicle somewhere other than the pick-up point.

I like cycle-touring with a smartphone. Can I get coverage in NZ?

Almost all of the North island has good cell coverage, and about half of the South island. It’s almost entirely 3G, with sections of LTE. The iPhone 5 will run at 3G speeds, and the iPhone 6 will run at LTE speeds when available. Either speed is more than fast enough to use Google Maps, make reservations, check weather, et cetera.

If you want to upload lots of photos you’ll want to wait until you get to a hotel. Almost all of them offer wifi internet access with some amount of free data, but be aware that for a person from the United States, the free data cap can seem absurdly small. Only a few hotels have unlimited free wifi, a few more have a nice 2GB limit, and the rest place their limit at around 200MB which is not enough to do much of anything except read email.

How much will smartphone coverage cost, and how can I arrange it?

T-Mobile actually has international data for NZ built in to their standard plan. You can just leave the country and the coverage will follow you. In practice, I’ve found that you get much lower data speeds than if you were traveling via AT&T or Verizon, probably because the host carrier puts your device in a lower service tier or something. But hey, it’s still a great deal.

You can also buy temporary roaming coverage for the duration of your trip, if you’re an AT&T or Verizon user.

For example, AT&T offers a multi-tiered package called “AT&T Passport” that covers New Zealand, via partnerships with Vodaphone and Spark. You pay up front for a given date range, and a certain amount of usage, and it starts automatically.

Be aware that if you have wifi at home or at work, your cellular data usage will spike sharply when you travel, because your phone won’t be switching to wifi nearly as often. A single software update or app download can easily blow through half your data if you’re not careful, and push you into the overage charges, which stack up quickly. (If you’re concerned about this, and don’t mind losing your usual phone number for a while, you can buy a SIM card when you arrive in NZ with a 2GB data cap. It will probably cost you about 1/2 of what AT&T charges for the same amount of data.)