The hardest day of riding ever (so far)

August 16, 2019 Filed under Amused, Introspection, Stress

The day started off very promising, with a rainbow. What could be more pleasant and gentle than that?

On the way out of town I had a chuckle at this bit of tourist-baiting:

The road looked clear and straight, but as soon as I turned north I slammed into a headwind. I geared down and put on my audiobook about the solar system, and turned those cranks like a workhorse, moving along at just a little over 2 miles per hour. This was going to be one of those “test of patience” days that every cycle tourist knows about.

Noon turned into afternoon. I saw some interesting geography, and took plenty of rest breaks to keep my spirits up and my bladder empty. It’s a real skill, being able to watch for traffic in two directions at once while peeing and turning with the wind. I’m sure this skill will come in handy. Maybe at parties — or job interviews!

Pedaling and pedaling, afternoon turned into evening. I wanted to ride around at least one of the two peninsulas between me and Siglufjörður. There was a campground at the end of the fjord between the peninsulas that I could crash at if it got too late — and it was getting pretty late already.

I took a break by the side of the road, ate some chocolate, and then just stood there for a while as the wind battered me. My waterproof clothing kept the cold out, so the effect was more like a very light massage. I took a few photos of the misty landscape, and then had a little dialogue with it in my mind. It’s that solo tour craziness setting in. I’ve felt it before!

At that point the wind kicked up so hard that it knocked my bike over. I cursed a bit, then carefully dragged Valoria upright and inspected her. No harm done. Taking that as a cue to keep moving, I sat down and started to pedal away. The rain immediately began to stab at my eyes. I reached for my sunglasses… Whoops; they were gone!

I did a U-turn on the road and looked back. Where had the bike fallen over? There were markers by the roadside every 20 feet or so, but the markers all looked the same. I pulled out my phone and went over the last few pictures I’d taken. There was a shot of Valoria by the road! Ah hah; I could compare it with the weeds growing on the shoulder.

On I rode, slowly rounding the first peninsula. It was close to midnight by the time the wind was finally at my back. I zoomed back up the fjord, looking forward to a nice rest at the campground. But where exactly was the campground?

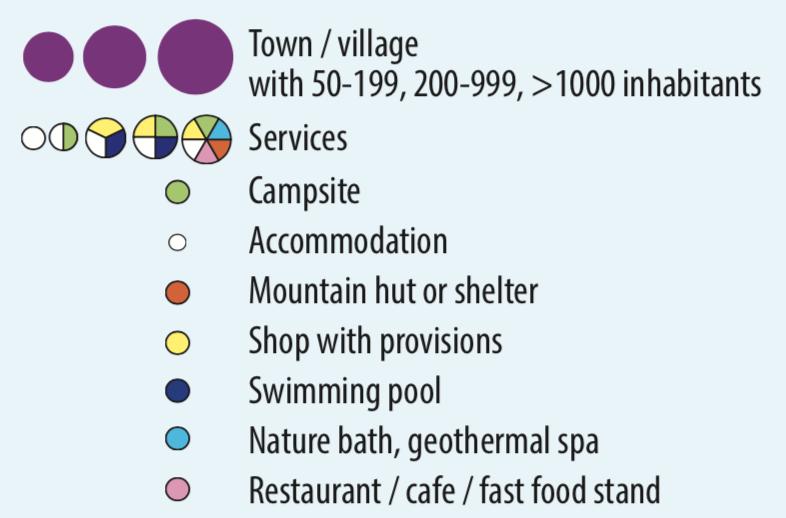

I checked my map. Supposedly there was a microscopic town here called Ketilás, with white and yellow dots on it. The white dot indicated a campground, so there should be one right about — uh oh. Let me check that map legend again…

Well that’s not good. The white dot means “accommodation”, and that usually means hotel or guesthouse, and those are usually very closed by now. I suppose I could try peeking in a few windows to see if someone is still awake, or even knock on the door and wake them up, but that would be pretty rude for a tourist. I could also try stealth camping, or just set up on somebody’s lawn and try to pack everything up early in the morning before they spotted me, but I’d sleep poorly and the next day of riding would be wrecked.

Thinking it over, I decided that I might as well just push forward to Siglufjörður, around the next peninsula. I would be getting there quite late. On the plus side, there was a tunnel between me and the town, and if I passed through it late at night I could avoid all the car traffic. And there’s also a chance that the wind would be quieter at night. I called up the Iceland Bicycling Map to check out the road around the second peninsula:

My location was right around that white dot at the bottom, and I was headed north. See that red and yellow triangle with the drawing of a windsock in it? That’s the section I was most worried about. If you look very closely you can see a bunch of yellow stripes coming off the side of the road, just below the triangle. That means “lots of very steep hills all crammed together”. It was not going to be easy.

But I’ve always been a night owl, and a little bit foolish with my solo adventures, and besides I had my headphones on and was playing a really funny episode of The Goon Show called “The House Of Teeth” and it matched with the misty, dark atmosphere of the fjord. Even the wind was cooperating. It was a pleasure to be out riding, even after so many hours. So why not continue?

The cloud cover got thicker, and the sky darkened to the point where it was like riding at night back home — close to the equator. The rain intensified and drove all the mist down to the ground. I crawled up a series of hills. Nothing I hadn’t dealt with many times in the past. This was going to be a late night but I could handle it.

Then I rounded a tight curve and the wind pounced on me, lashing me with claws of rain — left, then right, then left again. I had to move out into the center of the road just to give myself enough room to make course corrections as I got shoved around. Then I saw a sign. I couldn’t parse the Icelandic word on it, but the symbol of two squiggly horizontal lines made the meaning obvious: “Lots of very steep hills all crammed together.” The sign was posted at the bottom of an incline that vaulted up into the darkness so sharply that it seemed like the road had a crease in it. As I fought my way up to the base of this daunting new hill, headlights appeared behind me. I quickly moved to the narrow shoulder and put one leg down to brace myself, and gripped both handbrakes. There was no way I could trust this wind around even a single car, in either lane.

The car slowed and moved into the opposite lane as it passed. My lights and reflective gear were still doing their job. But it didn’t matter; I would still need to stop like this for every car, because now the wind could actually hit me hard enough to send me all the way across the road. This was going to slow me down even more.

I started up this latest hill, fighting hard against the wind, and had to stop about 20 meters up for another car. The shoulder was half as wide as my bike and fell off sharply even here on the inland side of the road. If I fell down it I would tumble over and over on the bike for who knows how long, then probably splash into a pool. Even if my body didn’t get twisted or broken I would never find all my gear again. I was bracing myself and contemplating this as the car passed me, and the vortex behind it pushed the wind away and then snapped it back again twice as hard, nearly driving me over the side and turning my imagination into a prophecy.

It would not do to linger. When I didn’t have to be on the edge of the road I should move back out into it. I resumed pedaling. Rain stung my eyes and even when I blinked it away the darkness cut visibility to the range of my headlight, which was only at half brightness because I could not go fast enough to keep it powered by the generator in my wheel. I could see maybe 15 meters ahead. And if I stopped to rest for more than a minute or so, the headlight would fade completely and I’d have to start up again in almost total darkness. No matter how steep the hills became, as long as I was climbing them I could only rest for about 30 seconds at a time. I was breathing hard constantly now. In a flailing burst of optimism I thought, “Hey, at least the air is fresh!”

Then I got serious. “Okay,” I thought. “This has passed into the range of conditions where even experts have accidents and get killed. This is not just dangerous. This needs another adjective tacked onto the word dangerous. This is extremely dangerous. In conditions like this it’s no longer a matter of if but a matter of when I will get hurt.”

But I couldn’t just sit there on a hillside bracing against the wind forever. Even if I tried to wait for just a little while for conditions to improve, I had to balance that against the fact that it cost me energy to stay in place. There was a tradeoff happening every time I stopped and it might not work in my favor. The one thing I was guaranteed to gain from waiting would be improved visibility, because eventually the sun would come up. But if I tried to wait until morning, I would be incredibly tired and would have to contend with far more traffic, and the wind and the rain could be even worse during the day as the sun beat on the clouds. There was no easy option here, and the clock was ticking.

I looked at my phone in case I needed to call for help: No signal.

I thought for a while as I rode, and decided that I would split my time between two things: Pushing forward along the route, and stopping to look around for a sheltered place to stealth camp, so I could get a night’s rest before finishing the ride. I was a little worried that the wind would drive rain inside my tent and I would be sleeping in a wet mess – very dangerous because of the cold it would bring – but if I found enough shelter and the wind didn’t make any extreme changes I could avoid that.

I made it to the top of the second steep hill after the roadsign, and started down. I had to apply the brakes constantly because it was dangerous to go any faster than about 15 miles per hour in such unpredictable wind: I could run right off the road before correcting my course. Then I had just enough time to see something worse in the headlight and squeeze the brakes like mad, dropping my speed down to almost nothing. The pavement ended. Right at the base of the hill the road became a mess of dirt, loose gravel, mud, and potholes. So many potholes that it was hard to believe. It was like someone had replaced the road with an art installation called “A Meditation On The Pothole And Its Infinite Forms,” and the artist had begrudgingly included just enough tiny threads of road surface to divide one pothole from another, and not a centimeter more.

With the wind bucking me about there was no way I could navigate between them, so I just blundered into the potholes – one after the other – hoping they weren’t too deep and fighting to keep my momentum. For the next mile at least, every time the road leveled out it would turn into this shotgun blast of potholes. Sometimes the road would reassemble itself into pavement for the next hill; sometimes not. And of course the road continued to swerve left and right as well, following the messy coastline. As it did, the hillside to my left would sharpen into a cliff and then come charging up to me, stopping just short of the road, then slink back again to some vague lump in the near-darkness. On my right, nameless temporary rivers split and reformed, then fed into pools below the shoulder or tumbled into choking drains. Somewhere below, about 50 meters down, the ocean thrashed at the rocks.

After some unknown amount of time, I spotted a weather station – two narrow towers of steel scaffolding with little boxes attached – erected on a prominence to my left. I knew from previous experience that weather stations always had little roads leading up to them, and the ground around them was usually cleared. Perhaps I could find shelter here and set up my tent?

I found the access road and parked my bike on it, then picked my way carefully along the little road towards the towers. The ground did level out, but the wind was still screaming across it. The road continued though, so I followed it for another 50 meters, hoping for a wrinkle in the hillside or a large rock that would give some shelter. Instead I found myself approaching a cliff.

Suddenly I stopped in my tracks. Here I was, in the dark and rain, a hundred meters from my bike, out of wireless range, in a foreign country thousands of miles away from anyone with any idea where I might be, and I was walking towards a cliff.

“Am I trying to commit suicide?” I thought.

I stood there, rolling the question around. Was this some kind of subconscious thing? Am I like one of those ants that gets a fungal infection, and the fungus creeps into its brain and compels it to climb up a blade of grass and wait to get eaten by a bird? Has this trip been part of a secret plan from the depths of my mind, to get to the most remote and unfindable place possible, under the cover of a storm, and drop myself into the sea?

I imagined myself as a little icon in a computer game, on a landscape made of tiles. “Age Of Adventure” perhaps. Step by step, my icon moved across the tiles of grass, towards the tiles of water, and then disappeared as it fell in, with a bleeping sound effect. Along the bottom of the screen appeared the words: “PLAYER HAS PAYED THE DEBT WHICH CANCELS ALL OTHERS.”

“… Nah,” I decided. “That’s pretty dumb. But I am making some strange decisions. The bike has food and lots of useful equipment and I should be sticking close to it. Time to turn around.” I about-faced and walked back up the access road, rejoined my bike, and continued fighting into the wind.

Another hour passed, much the same as the previous hour. My wireless signal was dead but I could still get GPS coordinates, and the dot on the map said I was almost done with the hills. I stopped and looked around near a very large boulder on the right side of the road that looked promising, but the ground around it was wet and soft. There was no way I could anchor the tent. Annoyed at myself for wasting more time, I climbed back on the bike. Finally, after nearly another hour – at this point it was 4:30 in the morning – I crested a final hill and a valley opened in front of me. I shot down into it, and over the next half hour as I pedaled across, the clouds broke up and the rain eased off. It looked like I was through the worst of it.

I climbed up the valley, then around a few more curves, and there ahead of me was a huge hole in the hillside, with yellow light spilling out of it. I had made it to the tunnel.

As I drew close to the opening, the wind made one more try to assassinate me, coming down the hill in a rush and driving me across the road. I rolled all the way to the opposite shoulder before I could compensate, and saw that I had nearly been blown over a cliff.

I was just at the entrance to the tunnel. According to the notes I’d made earlier, it was the Strákagöng tunnel, 800 meters long and built in 1967. Wide enough for one lane, with a few alcoves along one side for cars to pull over, making two-way travel possible. I could only see about 30 meters in before it curved to the right. It was lit by yellow sodium lamps and looked like the interior of a corrugated cardboard box that had been sitting outside for a month and started to buckle inward and decompose.

“This will be interesting,” I thought. Right next to me I saw this:

The number 42! (More or less.) Surely it was a sign!

No, I mean… Symbolically.

There wasn’t a car in sight. Time to get risky. I pulled out my phone and took a video to document my passage through the tunnel. Sped up 4 times it looks like this:

The walls of the tunnel are surprisingly organic-looking, until you get very close and see that you are looking at some kind of semi-rigid insulation that has been bolted onto the inside in large sheets, perhaps during some kind of retrofit. Water seeps in from the surrounding rock, making all the surfaces wet, and in places it runs down the insulation like the walls of a shower. Not being a structural engineer, I wasn’t sure if the insulation was there to prevent cave-ins, or to redirect water, or perhaps to absorb minerals and eventually turn into solid rock. But it was definitely not what I had been expecting. Coasting along it silently on my bike, with no one else around, it felt more like a Disneyland attraction than a piece of highway infrastructure. Maybe “Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride.” I kept expecting to see twinkling lights, or a fake mine cart filled with jewels off to one side, or cartoon-characters made out of foam rubber bounding across my path.

Then I was out, back in the open air. The rain was gone and replaced by a luminous fog, and the road began a long, straight descent, with a procession of tall sodium lamps guiding the way. I stopped turning the pedals and just cruised along. It felt like the road was rewarding me for all my efforts. Occasionally I would spot a sheep, tucked in next to the bushes on the side of the road, hiding from the wind. I imagined they were there to witness my passage and congratulate me on my victory against the hills. “Baa, baa, congratulations,” they were all saying. (Well, a few did say “Baa”, so maybe that counts.)

Just as the descent slowed I began passing the houses of Siglufjörður, and by the time I had to turn the pedals again I was almost in the middle of town next to the harbor. It was about 6:00am, and the sky was already light.

I threaded my way to the south edge of town, up a short hill. There was a campsite here, divided into several terraces etched into the hillside with a small wooden building perched at the top. It was just about full daylight and I could see at a glance that there was nobody camping there — not a single person.

I fought my way up the roughly cut grass to the highest terrace, and set up my tent next to a large bush. As far as I could tell it was the only place in the entire site that was truly safe from the wind, which was no longer howling but still uncomfortably strong. I used the toilet in the small building, refilled my water sack, and with only a little more exhausted fumbling than usual I assembled my tent and stowed my gear.

Laying half-curled in my sleeping bag, with my mask pulled over my eyes, I fought against the sudden insane idea that I was only hallucinating being safe and warm, and was actually lying mangled at the bottom of a cliff with my bicycle on top of me, somewhere back on the road, in the dark. Was I only imagining I was safe, to comfort myself as my senses failed? Did I really make it all the way through that hellish terrain, up the hill, through the tunnel, and down here to the campsite?

I pulled up my sleep mask. My eyes stung from the sunlight, and then I saw the plastic netting of my tent, vibrating from the wind.

“Well, if this is my imagination, I’m just going to have to go with it, because it’s way too vivid.”

Then I fell asleep.