Down To Beatty – Route

June 17, 2020 Filed under Uncategorized

June 17, 2020 Filed under Uncategorized

June 16, 2020 Filed under Uncategorized

June 14, 2020 Filed under Uncategorized

August 2, 2019 Filed under Uncategorized

June 24, 2019 Filed under Uncategorized

People with lots of hair don’t need to worry about the sun burning their heads. I’m not one of those people. I began losing my hair in high school. By the time I was in college it was easier just to shave it all off and be bald.

After college I got a series of jobs with microbiologists. They encouraged me to learn about DNA and genes. I also learned about the way ultra-violet light works to damage DNA.

Think of it like a hailstorm. Direct sunlight rains down on your skin, and little bits of UV light knock into the DNA* inside your skin cells and warp tiny pieces of it, like hailstones putting dents in a roof. It has nothing to do with temperature! It can be a cold, windy day, and the heat from the sun might feel great on your limbs, but that hailstorm is still happening, knocking DNA out of place.

The cells in your body are also filled with tiny little repair robots. When UV light breaks things, they find the little broken bits and repair them. When you’re young they work pretty fast, which is why kids can go running around in the sun for hours and the robots will keep up with the damage. Even so, if the sun is really intense, the damage will accumulate anyway and you’ll get a sunburn.

When you’re older, the little repair robots wear out, just like everything else. If you make them do lots of repairs, their decline is even faster. Your skin starts getting dry. Little spots appear, and cuts and bruises take much longer to heal. The key things is that it’s cumulative. You may get plenty of sunlight for years and look fine, and then one year you’ll discover that you’re crossing a threshold where all the little repair robots can’t keep up with even limited exposure, and damage will appear and then stay there, while more appears on top of that. The decline is not reversible.

( * Okay, technically most of the damage is done to the RNA in your cells, not the DNA. I’m making some simplifications here. But I need to say this or the scientists I work with will chase me down!)

Since I only have one “hairstyle” for myself at this point, and it depends on the skin on top of my head, I’ve become paranoid about covering my head (and a fair amount of my neck) with something that physically blocks UV light whenever I’m outside for more than a few minutes. I’ve been paranoid like this for about 15 years, and it’s paid off. I know people the same age and skin tone as me, who’ve been shaving their heads and then walking around outdoors for years, and their heads now look a bit like fried chicken.

I fully admit it: It’s almost entirely vanity that makes me do this. But there’s also a little part of me that knows I’m reducing my risk of skin cancer, and that part is grateful too. Thank you scientists, for compelling me to learn about this! My hat’s off to you folks! (WAIT, NO IT’S NOT.)

Anyway, the point of all that is: Covering my head is important to me, even when I’m wearing a bike helmet that’s full of holes. It’s especially important on bike tours, when I’m out in the sun for entire days, back to back.

Just about every bandana out there is good for filtering dust and maybe holding water, but is terrible at filtering out UV light. If you have one around your house, take it outside and hold it up in front of the sun. The sun will still be almost too bright to look at directly though the bandana. Put that on your head and you’re basically walking around wearing tissue paper. The thread count (the density of the weave) of your average bandana is 100 per inch or less — usually 75.

You don’t need something that completely blocks light. Something that scatters it will do fine, because the UV spectrum will get mostly absorbed in the process. The higher the thread count, the more scattering. For example, pillowcases usually have a thread count of at least 300. Hold one of those up to the sun and you’ll see a glow rather than direct sunlight. (In general a pillowcase would make a poor bandana because a 300+ thread count is not very breathable, and the tiny threads don’t hold water well.)

You can buy bandanas that claim to have a thread count of 300, but they’re always a polyester or cotton-polyester blend. I’ve found that if I sweat in any polyester thing for more than an hour, I start to stink. So those are no good for me.

For a while I thought the solution was to buy a cotton cloth dinner napkin and wear that like a bandana, but I tried a few and realized that the cloth was uncomfortably thick, and they were usually too small. What to do?

I went to a fabric store, and bought several yards of thick, supple cotton cloth. Then I walked across the street to a tailor and asked them to cut it into 22×22-inch squares and sew the edges with an “overlock” stitch pattern. (A simple job for any tailor.)

I came back two days later and picked up a pile of bandana-sized cloths.

Then it was time for the fun part: Coming up with a design to put on them!

I wanted all these things:

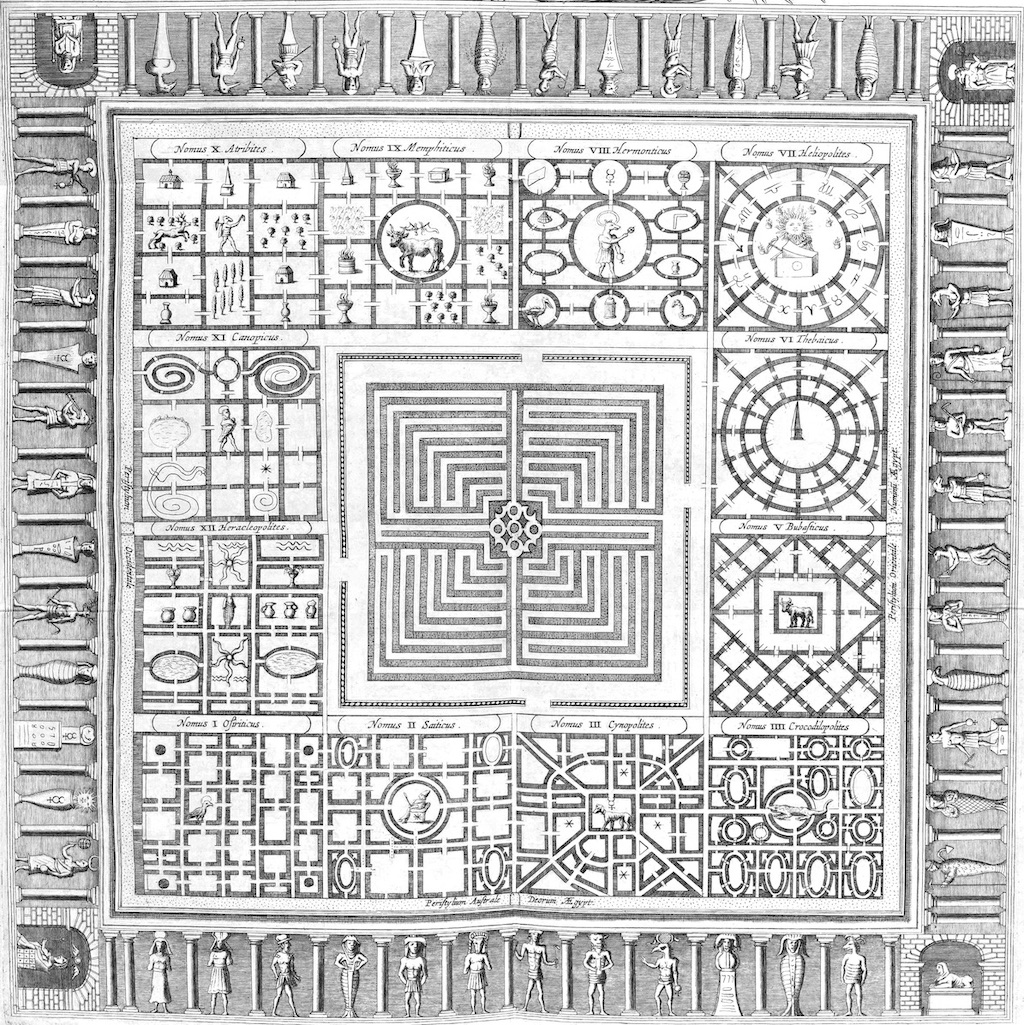

I’m fascinated by the work of early cartographers. After a lot of searching, I found this fanciful map of an Egyptian “labyrinth” at Hawara.

It’s supposedly based on a description of a real place by the Greek writer Herodotus, but I like it because it’s a beautiful example of how ancient maps were primarily artistic works, drawn from a culture’s collective imagination.

I’m tickled by the idea that I’m taking an ancient map, which claims to be accurate but is really almost total fantasy, and literally cloaking my head in darkness with it. Plus I like labyrinths.

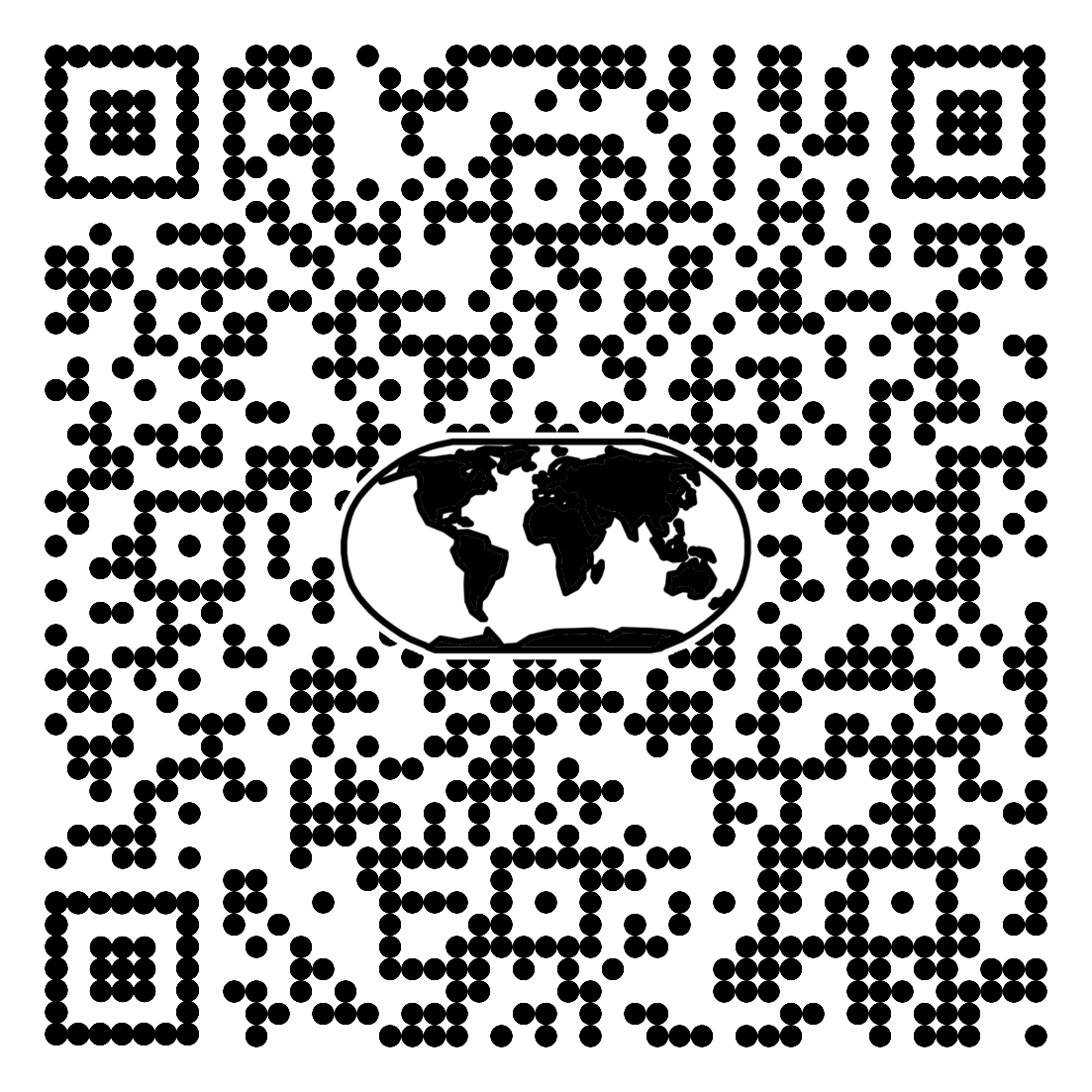

I’ve seen lots of clothing and tattoos that take words personally meaningful to the wearer and then obscure them in some cute way, usually by rendering them in another language that most people (possibly even the wearer) can’t read.

For many years in my home town there was a plague of young English speakers getting tattoos made of fake “Chinese” characters that supposedly meant “power” or “wisdom” or could even spell out the bearer’s name when strung together. All completely bogus, of course, but most people didn’t read enough Chinese to call them out on it — or those that did just silently scowled and looked the other way. I wanted to pay homage to that in an even stupider and geekier way: By pointlessly embedding a pithy quote into a QR code, only readable by a machine.

There are QR code generators online, so making one is easier than you’d think. Here are some test images I made:

The embedded quote is, “Sometimes you cannot find the truth unless you reach for it.” Hold your phone camera up to either one and chances are it will automatically appear!

Since the Egyptian labyrinth drawing is divided into convenient squares, I decided to add pieces of maps from computer games I played as a kid.

They blend in pretty well with the diagrams of fictional walls from 350 years ago.

What if I’m in the middle of some foreign country and my bicycle gets stolen, along with everything on it? And what if my phone and my wallet are on it too?

Chances are I’m still wearing my bandana. Written along the corners I’ll find useful things, including contact phone numbers for my relatives, an obfuscated credit card, and the encryption key for my backups.

After a bunch of Photoshop work, I had something pretty good:

The inspirational quote in QR code is different from the one I used for testing. Hold your phone up to the screen and see what it is!

With a good design in hand, it was time to get it printed onto the bandanas. Early experiments with a mail-order screen and my own ink were okay, but not great.

I decided to reach out to a local print shop called The Grease Diner. Could they make me a silkscreen big enough to fully cover a 22×22-inch bandana? Yes they could! I contacted JonJon and worked out an order for a large screen and some time on their press.

In a few days it was ready, and it looked beautiful.

JonJon helped me get everything aligned perfectly and I did six bandanas.

We pressed the printed bandanas in an iron to set the ink, and then JonJon gave me the stencil for safekeeping. Without his advice and help I’m sure I would have made a mess. Hooray for the Grease Diner!

The result was a bandana (plus a few spares) that blocks UV light, holds water on hot days, and is durable and soft. I’d happily wear it all over the world.