NZ Day 12: Bushwhackin’ Whakatane

OMG WATERFALL! HURF BURF DURF

In the morning the receptionist rang us on the hotel phone, and told us that the boat ride was definitely cancelled. We grumbled a bit, slept a while longer, and then decided to spend the day walking around Whakatane instead.

Whakatane is hemmed in on the east side by a long arm of brush-covered cliffs. In front of the cliffs is a low peninsula of land that pinches the ocean like a giant lobster claw, into a long narrow harbor. The Kohi Point Scenic Reserve encompasses the area beyond the cliffs, and the Nga Tapuwae o Toi Walkway track runs along the cliffs and provides lovely scenic views down into the harbor.

The Nga Tapuwaeo Toi walkway is where we’re headed today, since the weather has prevented us from going on a boat trip.

Even the steep ascent along the road to the trailhead is gorgeous, with plenty of odd vegetation to inspect!

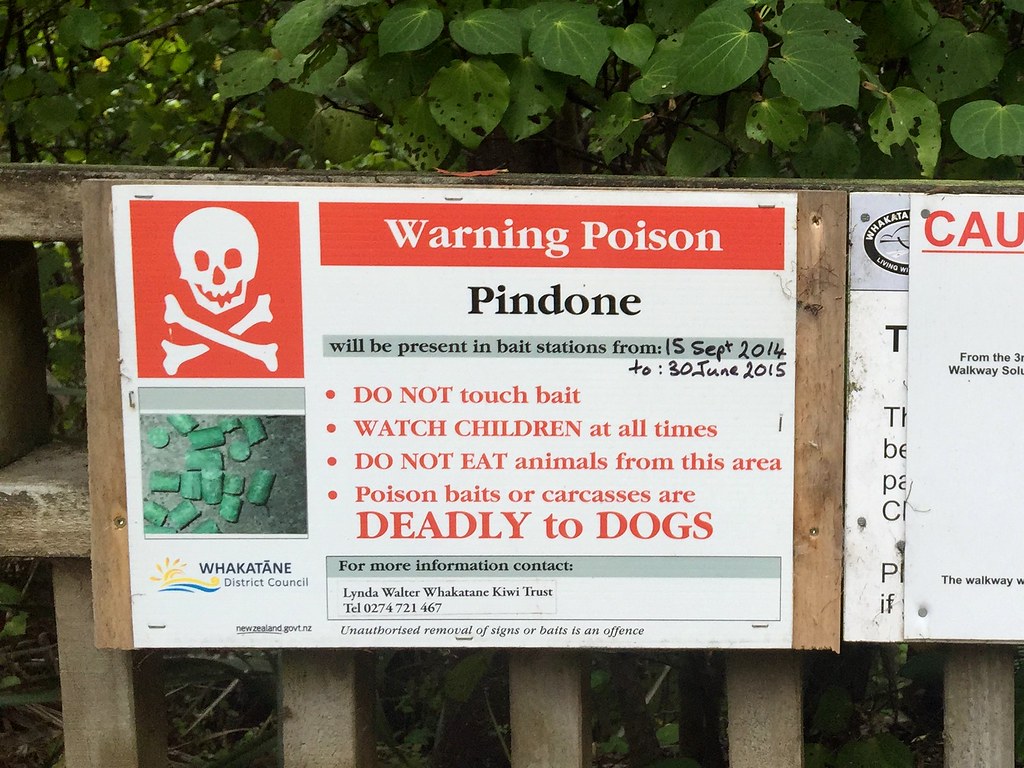

The government is serious about restoring the area for the eventual release of kiwi.

Dogs are especially frowned upon here, for the damage they can do to native birds, kiwi included.

In fact, the area has been sewn with poison, aimed at eliminating the local invasive predators, and the poison is a risk to dogs as well. If some arrogant vacationer brings their dog along this trail and the dog drops dead a few hours later, I imagine they won’t find much sympathy from the locals…

Here at the trailhead!

Here’s an example of one of the traps mentioned in the sign:

Every time I go on a long trip, there is some new shift in technology that changes the way I relate to the journey. Last time, while crossing the US, it was mobile mapping software. Everywhere I went, I not only knew where I was and what was around me, but what the locals thought about it. Everything had a star rating and a couple of reviews attached – hotels, restaurants, museums, parks, monuments, grocery stores, even graveyards – and often had photos as well, uploaded by patrons. I didn’t even need an itinerary, and I could still see interesting stuff and stay in nice places most of the time.

I think the big change for this New Zealand trip has been video recording. I had a video recorder on the last trip – a Countour GPS – but it was a complete pain to use. This time I brought a Garmin Virb with a dive case, and a tiny tripod for my phone to do time-lapse videos, and even though there was a learning curve for both, I got some really nice results.

So, I got to snorkel around the Poor Knights Islands, then a day later I got to see details I missed in the recording. I used the phone to get a nice time-lapse of us putting the bikes together, then used the Virb to get a nice time-lapse of our first ride around Whangarei. And now, on Day 12, I got to take some really neat ultra-stabilized time-lapse videos of our walk along the trail.

Checkit!

Smooth like buttah. I took these with an application called “Hyperlapse“. Here’s one descending the trail in the same area, later on the day:

It was a lot of fun taking these, and the six or seven others that I took as I was futzing around. The software uses the phone’s gyroscope and accelerometer to track exactly how you tilt and shake the camera as you’re recording, providing very accurate information to stabilize the image. Plus, the faster pace makes the videos less boring. Heh heh.

Here I am reviewing stabilized time-lapse movies on the trail! Couldn’t do that a few years ago. Had to take it home and crunch it in a video rig for a while.

We were enchanted by the amount of layered greenery, and the gentle misting of rain, and the complicated patterns of birdsong ringing out in all directions – and sometimes very close at hand.

After a while we encountered the first of several rest stops, but didn’t linger very long. More to explore!

Praying mantises are so cute! Look at those little folded arms, all ready to snap at some unsuspecting bug! KACHOW!!

One of the many many giant ferns in the process of uncurling.

Tai Chi Dork strikes again! This time, looking over the Whakatane inlet. That’s Moutohara Island, a.k.a. Whale Island, in the background.

We decided to turn back at this point, because the trail snaked along for another 20 miles and we didn’t have enough daylight to complete it.

Okay… Back in town, we saw this. Can somebody tell me why there appears to be a ramscoop-style air intake on this vehicle? Or is that something else? Is it for fording rivers?

We ended the day in style, with a movie and thai food. Since the weather was still messy we would probably miss the dolphin snorkel trip. Perhaps we should just leave town early next morning?