As usual before a big trip, I didn’t sleep well. Too excited.

I had a few extra minutes before I needed to hit the train station, so I got a donut and a mocha, to supplement the big chunks of bread I’d pilfered from the kitchen on the way out. The previous night I’d been watching the South Park episode “All About Mormons” while trying to repair my camping light, and the song was now bouncing all over my sleep-deprived brain. I couldn’t remember the lyrics though. As I rode to the train station I sang:

Transporting a bicycle on the train is so much easier than transporting one by air, it’s almost disorienting. You just get a luggage tag for it like any other piece of luggage, and make sure you’re early in line to load the bike on the train so the attendant has time to prepare.

Take your bags off and carry them with you, or check them too if you like. That’s it. No box and no disassembly required. (I assume this is because the train service is terribly under-utilized right now due to COVID-19, because the regulations state that you need some kind of bike carrier box. I asked the clerk about it the day before and he said a box would not be needed.)

I’d purchased a little private room, because I wanted a safe place to stick five big chunks of luggage, and some relative isolation from the other passengers. It wasn’t much more expensive than a regular ticket, and the table was helpful for getting work done.

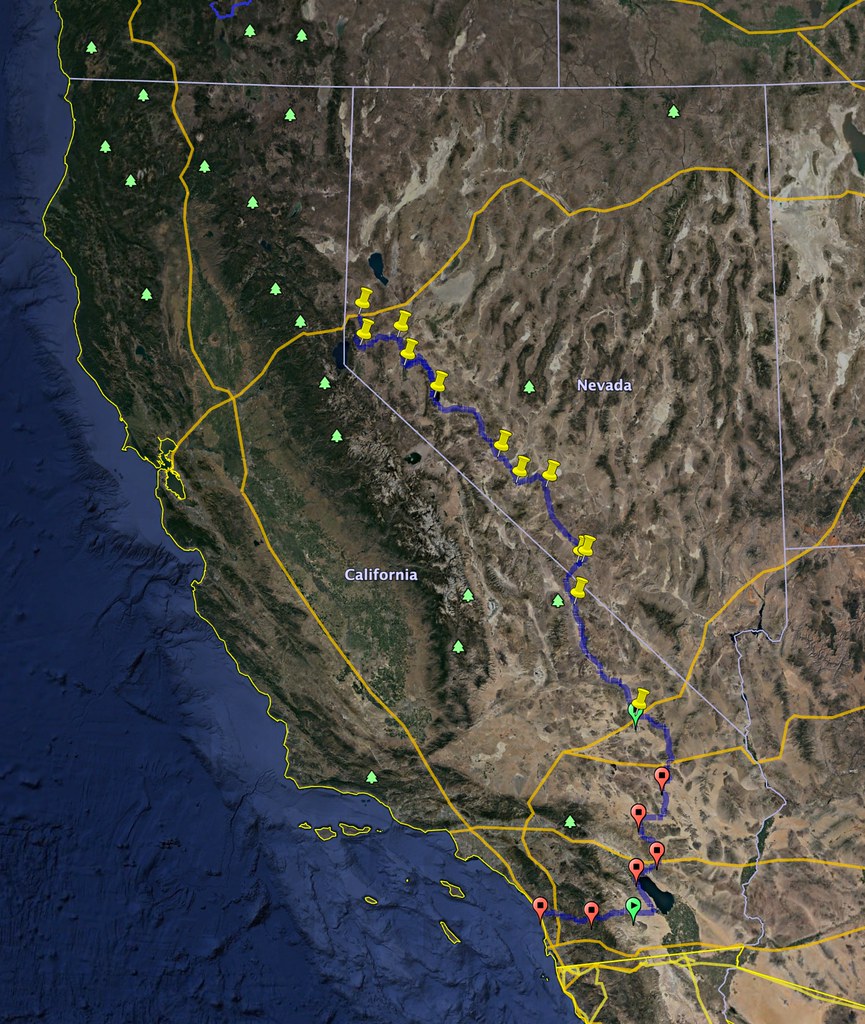

All I had to do was sit, and the landscape slowly transformed outside the window until I was in Reno:

The ride was quite pleasant, though there was a dark spot. I could overhear someone playing a talk show on their phone with the volume turned way up. The little speaker carried right through the wall. It was some obviously right-wing pundit screaming at the top of his lungs, about how Democrats are ruining the country because they’re saying there’s systemic racism.

“What systemic racism?” screamed the pundit. “The officer who killed George Floyd was arrested and charged with murder! The system obviously works! What are these people complaining about?”

What? That didn’t make sense. The pundit was either deliberately not mentioning, or just plain ignorant, that all the repercussions for Floyd’s death have come about because the four police officers who pinned him down were recorded by onlookers, who then raised hell. No recording, no uproar. One of the officers even tried to prevent the recording, by ordering the onlookers to stop, then brandishing pepper spray.

This is all aside from the fact that Floyd was being arrested on suspicion of using a counterfeit bill at a nearby market. That’s not even a violent crime; not even close. If I write a bad check, I get a 35 dollar fine. George Floyd was strangled slowly to death face-down in a public street by the police for the equivalent.

This information is everywhere online and trivial to verify. And yet, I’m hearing this talk show pundit have a full-scale 100-meter freestyle whimpering hissy-fit, which goes on for half an hour, based on an ignorance of the facts that it would have taken him 30 seconds on a smartphone to dispel. How could it be anything but deliberate?

“The Democrats want these protests to happen! They want the looting to happen! They don’t care if the whole police force gets defunded and the country sinks into anarchy, they just want Republicans to die. This is a war on white middle class people and it’s based on lies!”

Deliberate construction of an enemy, blaming it for every problem, stoking fear and impotent rage. What people are drawn to this? Why do they take it in? What do they get for spending hours absorbing it?

These are the times we live in. Honestly, I’d feel much better if the passenger on the other side of the wall was just watching porn.

I put in my headphones and ignored the voice. Then the ride was great again. I only left the compartment twice to use the bathroom, and wore my mask and washed my hands thoroughly each time. Getting sick is no way to start a bike trip!

I could tell when I was getting close to Reno because the number of hidden homeless camps sharply increased.

At the Reno station, I marched out to the platform with my bags. The man at the luggage car already had my bike at the doorway, and he handed it down to me. And just like that, I was in Reno with all my gear! Why do I travel on airplanes…?

Outside the air was fresh and it was only 88 degrees. I rode around a bit to orient myself.

The main drag was a forest of construction cones. Looks like the city is jumping on the chance to get a lot of work done while people are away.

I rode southeast for a little while and checked into a sorta-sketchy hotel near a mexican restaurant, then got some to-go food and munched it while watching a documentary on the Vietnam War. It seemed appropriate for the times.

{"lat":[39.52849664,39.52857099,39.52874667,39.52863377,39.52852103,39.52870074,39.52884767,39.52900198,39.52922746,39.52943097,39.52960674,39.52990069,39.53005785,39.5300224,39.53025382,39.53018199,39.53023982,39.53022532,39.53019775,39.53010169,39.53001292,39.52985442,39.52968435,39.52951948,39.52918613,39.52901254,39.52874307,39.52865514,39.5284813,39.52821635,39.52797294,39.52780563,39.52761101,39.52739702,39.52719484,39.52699703,39.52685202,39.52672546,39.52665161,39.52650015,39.52629446,39.52613805,39.52594745,39.52577168,39.52561636,39.52546549,39.52529576,39.52513952,39.52500608,39.52477868,39.52460777,39.52441423,39.52424919,39.52398315,39.5237995,39.52361602,39.52345224,39.52329223,39.52317262,39.52290381,39.52269997,39.52245337,39.52225782,39.5220331,39.52186739,39.52182724,39.52165424,39.52145525,39.52132952,39.52118116,39.52090423,39.52071572,39.52046812,39.52031674,39.51973571,39.51957318,39.51937914,39.5190271,39.51831774,39.51814893,39.51768071,39.51728601,39.51678251,39.51658486,39.51622201,39.51596167,39.51558775,39.51541936,39.51526237,39.51499088,39.51487512,39.51454278,39.51418915,39.51400693,39.51375899,39.51353997,39.51338683,39.51290295,39.51271896,39.51229358,39.51196719,39.51180022,39.51142371,39.51117342,39.51103336,39.51083555,39.51055735,39.51043213,39.51026809,39.51008721,39.50989636,39.50971799,39.50952671,39.50936729,39.50917694,39.50892573,39.508655,39.50848694,39.50793793,39.50774011,39.5074268,39.50720392,39.50706822,39.50690486,39.5067254,39.50654787,39.50591847,39.50563843,39.50516276,39.50483981,39.50469421,39.50455532,39.50424804,39.50400002,39.50383867,39.50361789,39.50324406,39.50304658,39.50282957,39.50249782,39.50222163,39.50202944,39.50143692,39.50102478,39.50048071,39.49978284,39.49950372,39.49873803,39.49861037,39.49846763,39.49807259,39.49777738,39.4975038,39.49733641,39.49719191,39.49696744,39.49665488,39.4962844,39.49579037,39.49526524,39.49503893,39.49486174,39.4946159,39.49407711,39.4939404,39.49371032,39.49359615,39.49369489,39.4938632],"lon":[-119.81198036,-119.81212503,-119.81238881,-119.81224967,-119.81240323,-119.81244036,-119.812507,-119.81255025,-119.81250171,-119.8125484,-119.8126168,-119.8126738,-119.81274923,-119.81301402,-119.81298787,-119.81315115,-119.81337201,-119.81361408,-119.81383201,-119.81406745,-119.81419134,-119.81413845,-119.81416519,-119.81412856,-119.81404507,-119.81402504,-119.81400141,-119.81386218,-119.81382145,-119.81381357,-119.8137041,-119.81364459,-119.8136145,-119.81356999,-119.81349648,-119.81345273,-119.81339405,-119.81329858,-119.81298259,-119.81289684,-119.81287689,-119.81280355,-119.81275384,-119.81278578,-119.8127209,-119.81267371,-119.81259702,-119.8124666,-119.81239619,-119.81227582,-119.81221933,-119.81218035,-119.81210827,-119.81195337,-119.81199495,-119.81192948,-119.81182429,-119.8117657,-119.81167601,-119.81162262,-119.81157032,-119.81141408,-119.81139036,-119.81126622,-119.81124032,-119.81104989,-119.8109628,-119.81088811,-119.81081083,-119.81075023,-119.81064077,-119.81055259,-119.81045469,-119.8103588,-119.81004079,-119.80996778,-119.80989779,-119.8097118,-119.80937828,-119.80926613,-119.80906379,-119.80884846,-119.80861913,-119.80850338,-119.80826299,-119.80818177,-119.80800332,-119.80793132,-119.80780467,-119.8076387,-119.80750526,-119.80746536,-119.80733301,-119.80724953,-119.80715046,-119.80704065,-119.80694049,-119.80674402,-119.80664478,-119.8064307,-119.80628721,-119.80618838,-119.80603969,-119.80590633,-119.8058412,-119.80572377,-119.80561263,-119.80553518,-119.80544851,-119.80537727,-119.80528347,-119.80524542,-119.80514249,-119.80507585,-119.80498516,-119.80485205,-119.8047368,-119.80464142,-119.80438091,-119.80427412,-119.80412987,-119.80400682,-119.80393851,-119.80388369,-119.80380842,-119.80375528,-119.80344121,-119.8033532,-119.8030937,-119.80294081,-119.80289128,-119.80279681,-119.80263873,-119.80252398,-119.80246204,-119.80234059,-119.80218259,-119.80206968,-119.80198746,-119.80181613,-119.80168873,-119.80158529,-119.80129788,-119.80108146,-119.80081868,-119.80045558,-119.80032248,-119.79994001,-119.79985376,-119.79980003,-119.79964371,-119.799521,-119.79935512,-119.79921984,-119.79914339,-119.79905899,-119.79888716,-119.79867015,-119.79844887,-119.79824619,-119.79814955,-119.79806271,-119.79795928,-119.79768695,-119.79775158,-119.79776641,-119.79787747,-119.79774353,-119.7978043],"el":[1317.4,1317.0,1317.0,1317.4,1317.4,1318.4,1317.8,1317.8,1317.8,1317.4,1317.4,1317.6,1318.0,1318.2,1318.4,1319.0,1319.0,1319.4,1319.6,1319.6,1319.6,1319.4,1319.2,1319.6,1319.2,1319.4,1319.2,1319.2,1319.0,1318.8,1319.0,1319.0,1319.0,1318.8,1318.8,1318.4,1318.2,1318.6,1317.8,1318.0,1318.2,1317.6,1317.2,1317.0,1317.0,1317.4,1317.4,1318.6,1318.2,1317.2,1316.6,1317.4,1317.4,1318.2,1318.4,1318.4,1318.6,1318.6,1318.6,1319.8,1319.6,1320.2,1320.6,1320.4,1320.4,1319.8,1320.0,1320.8,1321.0,1320.4,1320.0,1320.4,1319.8,1319.2,1318.0,1316.6,1315.6,1311.6,1309.8,1310.4,1310.2,1310.0,1309.2,1309.0,1308.8,1309.4,1308.8,1308.8,1309.2,1309.2,1309.4,1309.0,1308.6,1309.2,1309.2,1309.6,1309.6,1310.0,1310.0,1310.0,1309.2,1309.0,1308.8,1308.2,1308.2,1307.8,1308.0,1307.6,1307.6,1307.6,1307.8,1307.6,1307.4,1307.2,1306.8,1306.6,1306.8,1307.0,1307.0,1306.4,1306.6,1307.0,1306.8,1306.8,1306.6,1306.4,1306.6,1306.6,1306.4,1306.6,1306.2,1306.4,1305.8,1305.4,1305.6,1306.2,1305.6,1305.6,1305.6,1305.8,1305.2,1305.6,1305.8,1305.4,1305.2,1305.2,1304.6,1304.4,1304.6,1304.8,1305.4,1305.4,1305.0,1305.0,1304.8,1305.0,1305.0,1305.6,1305.4,1305.2,1305.2,1305.0,1305.0,1304.4,1305.0,1306.0,1305.2,1305.0,1306.4],"t":["2020-06-02T23:04:08+00:00","2020-06-02T23:04:27+00:00","2020-06-02T23:04:34+00:00","2020-06-02T23:05:14+00:00","2020-06-02T23:05:37+00:00","2020-06-02T23:05:57+00:00","2020-06-02T23:06:05+00:00","2020-06-02T23:06:12+00:00","2020-06-02T23:06:26+00:00","2020-06-02T23:06:37+00:00","2020-06-02T23:06:48+00:00","2020-06-02T23:07:03+00:00","2020-06-02T23:07:14+00:00","2020-06-02T23:07:25+00:00","2020-06-02T23:08:11+00:00","2020-06-02T23:08:30+00:00","2020-06-02T23:08:39+00:00","2020-06-02T23:08:48+00:00","2020-06-02T23:09:00+00:00","2020-06-02T23:09:12+00:00","2020-06-02T23:09:23+00:00","2020-06-02T23:09:35+00:00","2020-06-02T23:09:58+00:00","2020-06-02T23:10:09+00:00","2020-06-02T23:10:21+00:00","2020-06-02T23:10:28+00:00","2020-06-02T23:10:39+00:00","2020-06-02T23:10:41+00:00","2020-06-02T23:10:46+00:00","2020-06-02T23:10:54+00:00","2020-06-02T23:11:07+00:00","2020-06-02T23:11:13+00:00","2020-06-02T23:11:22+00:00","2020-06-02T23:11:31+00:00","2020-06-02T23:11:43+00:00","2020-06-02T23:12:18+00:00","2020-06-02T23:12:25+00:00","2020-06-02T23:12:34+00:00","2020-06-02T23:12:40+00:00","2020-06-02T23:12:48+00:00","2020-06-02T23:12:57+00:00","2020-06-02T23:13:04+00:00","2020-06-02T23:13:23+00:00","2020-06-02T23:13:37+00:00","2020-06-02T23:13:48+00:00","2020-06-02T23:14:06+00:00","2020-06-02T23:14:48+00:00","2020-06-02T23:15:00+00:00","2020-06-02T23:15:07+00:00","2020-06-02T23:15:17+00:00","2020-06-02T23:15:23+00:00","2020-06-02T23:15:30+00:00","2020-06-02T23:15:38+00:00","2020-06-02T23:15:56+00:00","2020-06-02T23:16:30+00:00","2020-06-02T23:16:40+00:00","2020-06-02T23:16:50+00:00","2020-06-02T23:17:03+00:00","2020-06-02T23:17:11+00:00","2020-06-02T23:17:26+00:00","2020-06-02T23:17:36+00:00","2020-06-02T23:17:58+00:00","2020-06-02T23:18:11+00:00","2020-06-02T23:18:21+00:00","2020-06-02T23:18:34+00:00","2020-06-02T23:18:41+00:00","2020-06-02T23:18:48+00:00","2020-06-02T23:18:56+00:00","2020-06-02T23:19:02+00:00","2020-06-02T23:19:11+00:00","2020-06-02T23:19:24+00:00","2020-06-02T23:21:54+00:00","2020-06-02T23:22:02+00:00","2020-06-02T23:22:06+00:00","2020-06-02T23:22:19+00:00","2020-06-02T23:22:22+00:00","2020-06-02T23:22:25+00:00","2020-06-02T23:22:30+00:00","2020-06-02T23:22:40+00:00","2020-06-02T23:22:43+00:00","2020-06-02T23:22:51+00:00","2020-06-02T23:22:58+00:00","2020-06-02T23:23:07+00:00","2020-06-02T23:23:11+00:00","2020-06-02T23:23:19+00:00","2020-06-02T23:23:25+00:00","2020-06-02T23:23:35+00:00","2020-06-02T23:23:40+00:00","2020-06-02T23:23:46+00:00","2020-06-02T23:23:55+00:00","2020-06-02T23:24:00+00:00","2020-06-02T23:24:11+00:00","2020-06-02T23:24:23+00:00","2020-06-02T23:24:30+00:00","2020-06-02T23:24:38+00:00","2020-06-02T23:24:45+00:00","2020-06-02T23:24:50+00:00","2020-06-02T23:25:07+00:00","2020-06-02T23:25:15+00:00","2020-06-02T23:25:30+00:00","2020-06-02T23:25:39+00:00","2020-06-02T23:25:44+00:00","2020-06-02T23:25:54+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:01+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:05+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:11+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:19+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:23+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:28+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:33+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:40+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:46+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:51+00:00","2020-06-02T23:26:55+00:00","2020-06-02T23:27:00+00:00","2020-06-02T23:27:06+00:00","2020-06-02T23:27:12+00:00","2020-06-02T23:27:16+00:00","2020-06-02T23:27:34+00:00","2020-06-02T23:27:39+00:00","2020-06-02T23:27:48+00:00","2020-06-02T23:27:55+00:00","2020-06-02T23:27:59+00:00","2020-06-02T23:28:03+00:00","2020-06-02T23:28:07+00:00","2020-06-02T23:28:11+00:00","2020-06-02T23:28:30+00:00","2020-06-02T23:29:12+00:00","2020-06-02T23:29:25+00:00","2020-06-02T23:29:34+00:00","2020-06-02T23:29:38+00:00","2020-06-02T23:29:42+00:00","2020-06-02T23:29:50+00:00","2020-06-02T23:29:56+00:00","2020-06-02T23:30:00+00:00","2020-06-02T23:30:06+00:00","2020-06-02T23:30:15+00:00","2020-06-02T23:30:20+00:00","2020-06-02T23:30:26+00:00","2020-06-02T23:30:35+00:00","2020-06-02T23:30:42+00:00","2020-06-02T23:30:47+00:00","2020-06-02T23:31:02+00:00","2020-06-02T23:31:13+00:00","2020-06-02T23:31:28+00:00","2020-06-02T23:31:45+00:00","2020-06-02T23:31:52+00:00","2020-06-02T23:32:10+00:00","2020-06-02T23:32:14+00:00","2020-06-02T23:32:18+00:00","2020-06-02T23:32:29+00:00","2020-06-02T23:32:38+00:00","2020-06-02T23:32:47+00:00","2020-06-02T23:32:52+00:00","2020-06-02T23:32:56+00:00","2020-06-02T23:33:02+00:00","2020-06-02T23:33:11+00:00","2020-06-02T23:33:22+00:00","2020-06-02T23:33:35+00:00","2020-06-02T23:33:50+00:00","2020-06-02T23:33:57+00:00","2020-06-02T23:34:03+00:00","2020-06-02T23:34:11+00:00","2020-06-02T23:34:27+00:00","2020-06-02T23:34:36+00:00","2020-06-02T23:35:13+00:00","2020-06-02T23:35:19+00:00","2020-06-02T23:35:31+00:00","2020-06-02T23:36:44+00:00"],"spd":[0.785883707171,2.5303369957,2.35420106893,0.612525395978,0.902774928665,1.59071399832,2.33897863586,2.16403608278,1.95462514874,1.97450199651,2.03148747115,1.95105773481,1.89705138326,1.32997864706,0.706095624009,1.53755798564,2.27090488675,1.94845886217,1.74297098716,1.61282172991,1.41912920742,1.17378272142,1.26119939108,2.42144883432,2.96066665579,2.7524688256,5.22930441439,5.82927482548,3.81053361011,2.94702090697,2.71253432811,2.82156101651,2.55251199044,2.31432577602,1.29312189908,1.52714507539,2.11379776838,3.26928076868,3.5134037362,2.42561848688,2.59888995457,1.89285302544,1.27531372484,1.53137827528,1.30573900122,0.718236791588,1.10156560932,2.00926994173,2.51395811817,3.00500148402,3.19536860818,2.77008857542,2.1137512661,1.20729262684,1.3644310858,2.07660489999,1.72927136217,1.67325213632,1.97125476383,2.16650903711,1.85117062101,1.53560128987,2.20069742276,2.07427774764,1.92624391261,2.68735119943,2.91793188694,2.73311281778,2.25348152668,2.202230275,1.3140414948,1.87578270585,4.14707147098,5.04638513702,5.90061525854,6.94044218037,7.99126760003,8.4516374962,7.72167623557,6.95465380787,6.83895705876,6.70583498432,6.31881702809,5.85318781369,5.3196898544,4.70254296598,4.19185877757,3.68952779893,3.57203594311,3.58095138567,3.41351734638,3.39625633695,3.24466032022,3.34246576529,3.67260075682,3.77693368856,3.56968871776,3.04673292733,3.07974570945,3.82517152076,4.17536175942,4.23420204308,4.34294532042,4.22272156989,4.08914302048,4.04404722557,3.95674806064,3.90325871355,4.07641926375,3.72747279187,3.30003518498,3.9826333257,4.6365841907,4.58890507157,4.77559093527,5.16115429277,5.196530579,4.36087079918,4.19409212153,4.44253478902,3.98278512618,3.95232636261,4.37392831905,4.97289232039,5.16025846483,4.51120661046,2.35761554876,2.5915403422,4.33602698146,4.22159499115,4.2780057194,4.48322923531,4.74368324549,4.78495012859,4.56723117343,4.65748323801,4.83473428301,4.50013467648,4.30598107594,4.54004490937,4.64839238391,4.66454402731,4.59776979737,4.4046827339,4.61667027692,4.82742042992,4.90272102711,4.54091489863,4.07190618153,4.15863671502,4.00749670442,3.7854135992,4.06412579904,4.36799340964,4.34022687457,4.2680070184,4.15715099009,4.2954016529,4.27116836474,3.92783691158,3.65209282425,3.55574084573,3.81023434364,2.91252015059,1.24739950079,1.67279985725,1.98906855849,0.796635004593,0.134155027882]}