NZ Day 24: Tongariro Crossing!

Up at dawn’s crack with our backpacks and snacks! The weather was looking ominous but the shuttle driver claimed it would clear up and get warmer later in the day, so we boarded the shuttle with a handful of other explorers.

When we unloaded at the base of the trail, we immediately met a park ranger. Her purpose was to quickly examine the people starting the hike, and stop the ones that looked like they weren’t prepared well enough, and sternly warn them to turn around and leave. She was not as optimistic about the weather as our shuttle driver had been, and her information was more up-to-date.

“With wind chill, the temperature up there will drop below freezing,” she said. “And the wind will be blowing all the time.”

A few people turned around. Plenty of other people hurried by, as if they were trying to sneak past the ranger without being noticed — as if they were sneaking past a bouncer to get into an exclusive club. I spotted a young couple dressed in shorts, the boy charging up the trail with selfish bravado carrying only a water bottle, and the girl trailing nervously behind him with a fanny pack. She threw a glance back at the ranger but clearly didn’t have the guts to stop her boyfriend from making them both miserable.

And they surely would be miserable. Hours later Kerry and I would pass by clusters of people hunched behind rocks, their exposed skin turned purple, trying to decide what to do now that they were miles from civilization and anything warm.

We didn’t want to interfere with the ranger’s work, so we chatted with her just long enough to get news about the weather. Then we stepped onto the causeway and began the hike!

The causeway zigzagged to the east over alpine tundra, across tiny slow-moving streams and clusters of fragile-looking succulents and grass.

Most of the rocks were rough and porous, and they quickly became boulders as we went along.

As the route got steeper, Kerry and I remembered all our conversations with the locals about roads and bicycling and hiking trails. We decided that New Zealanders were so used to going up and down hills that they eventually stopped noticing them, and only remembered that a given route involved climbing when it went straight up an actual mountain. A while back we asked one of them to describe the Tongariro Crossing and he actually used the words, “It’s flat all the way up.”

Flat all the way up. That’s some serious “ancient Greek philosopher” logic, there.

While pondering the terrain’s obvious non-flatness, we posed for a couple of dramatic photos with Mt Ngauruhoe – a.k.a. Mt Doom – in the background.

The trail continued towards the left-hand flank of the mountain, and soon the stairs began.

At first it was little sections of stairs, a dozen steps at a time, and then we reached a rest area with some pit toilets and beheld one extremely long staircase that went lurching up the shoulder of Mt Ngauruhoe towards an unseen plateau to the north. Small groups of people were standing around trying to reach consensus over whether to continue, or turn back. Other people were just hunkered down eating snacks.

It was interesting to see how people dealt with the extreme weather. By this point most of the people with inadequate gear had been filtered out. We spotted a trio of older ladies who looked like they were in their late 60’s, each carrying a heavy pack. They had thick clothing but it was too porous to block the intense wind, so they compensated by moving quickly. I was more the plodding, cautious type, and spent a lot of time standing aside so other people could pass by without breaking their pace. It was a constant reminder that I wasn’t nearly as in-shape as I imagined.

The trail split, offering a partial route up the side of Mt. Ngauruhoe for the especially brave, but Kerry and I skipped it. A while later we met up with a group who made the climb, and they expressed disappointment that the peak was drowned in mist when they reached the top.

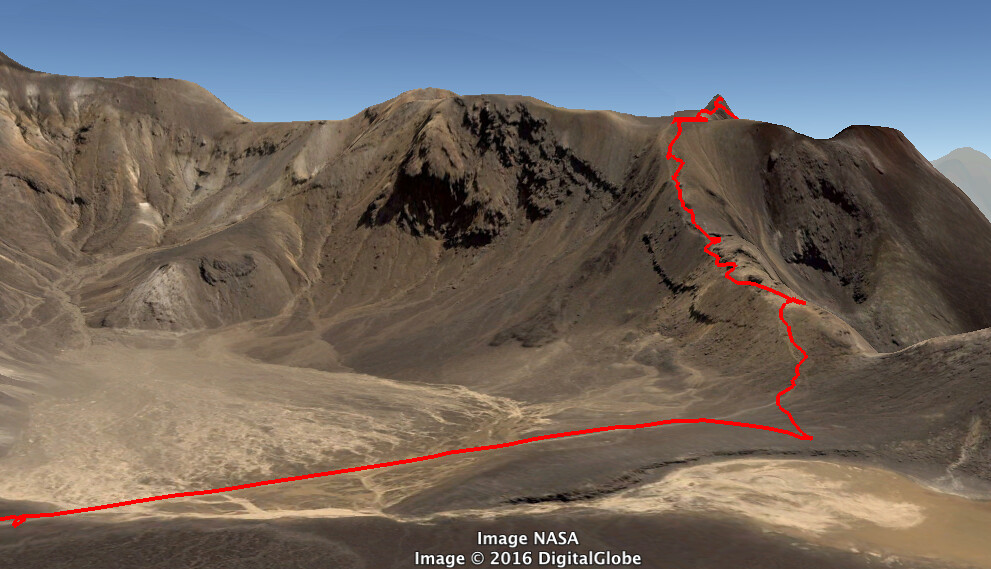

We followed the trail straight ahead, across a wide, flat plateau. The wind was still bitterly cold. Ahead of us we could see a hillside scattered with the bright dots of people in hiking gear, zig-zagging up to the top of a ridge, then following the ridge to a peak way up on the left.

Here’s a line showing the route:

Once we got up on the ridge we took a few shots looking back:

We climbed, then rested for a while in the shelter of some boulders on the ridge. Anyone around us who wasn’t resting out of the wind was getting more tired instead of less, and we heard plenty of tense muttering around us as clusters of people tried to decide whether to turn back. It was safe to assume that almost every one of the hundreds of hikers around us was doing this hike for the first time – like us – and wasn’t completely sure how much rough terrain lay ahead. (In retrospect, we were about a third of the way along the crossing.)

The trail got narrower and more hazardous. Cables were attached to the rock wall in some places, and we used them gratefully.

When we followed the ridge all the way to the top, we could see the Emerald Lakes down the other side, to the north. The trail also split off to the west, and to the east we could look down into a steep crater — the remains of a huge volcanic explosion.

We were standing on the top of Mount Tongariro – or at least, the highest remaining peak of it, after the top was blasted off long ago. The Tongariro crossing is actually named after this mountain, and the volcanic complex surrounding it. Even the much taller Ngauruhoe (Mt Doom) behind us – is technically just a vent of the Tongariro complex.

Even before the view, the first thing we noticed was the wind. It was up to 40 miles per hour, and it blasted us continuously from the north. We had to be careful to lean in that direction no matter which way we were actually walking.

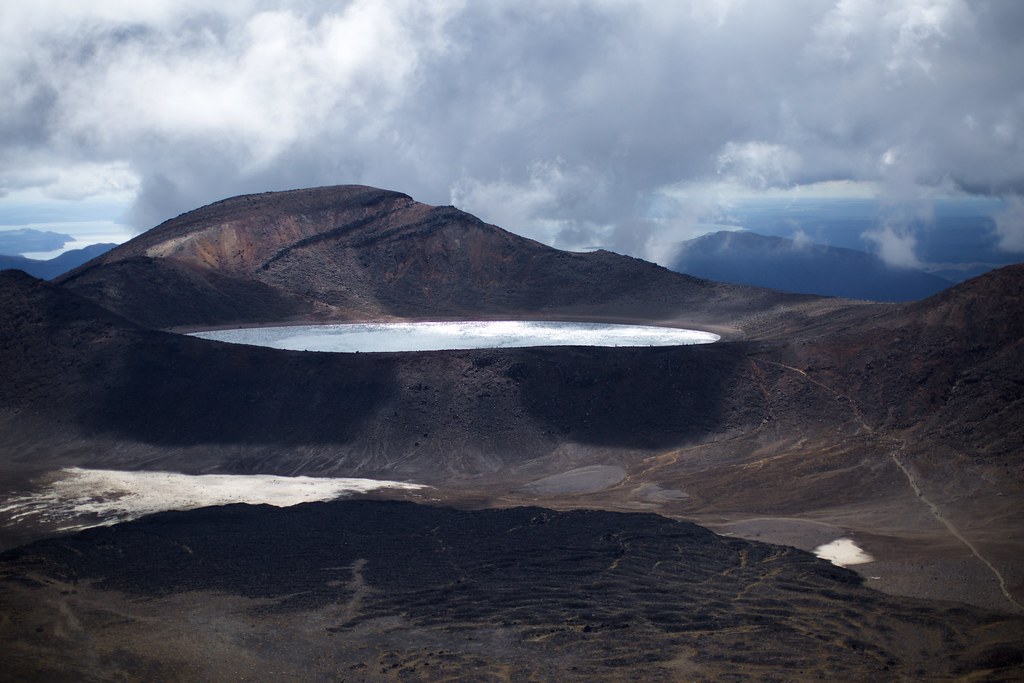

In the distance we could see the shimmering, chilly surface of Blue Lake. What a view!

Some hikers were taking the more ambitious western trail, which continued along the top of the ridge and bent around to the south, eventually returning them to the brutal staircase and the shuttle station. We followed the majority, stomping and slipping our way down the loose rock towards the Emerald Lakes.

This descent was tricky. Kerry couldn’t go four steps without slipping, and some other people were slipping and falling constantly, dropping their butts and hands into the soil. It looked painful. I went down the way I would on the chalk hills near my childhood home: Turned sideways, planting my heels very heavily to dig in each step. I didn’t fall over but I got a huge pile of gravel in my shoes!

The lakes grew more enchanting as we approached them. Soon we could see their strange coloring and watch the mist percolating and oozing out from the hills around them.

We went right down to the shore, then sat around resting and drinking the water we brought with us. I gobbled a bunch of snacks from my backpack. Kerry discovered that there was exactly one boulder in the whole area large enough to provide cover to pee behind, and when she went around it she found wads of toilet paper everywhere. Eeeew.

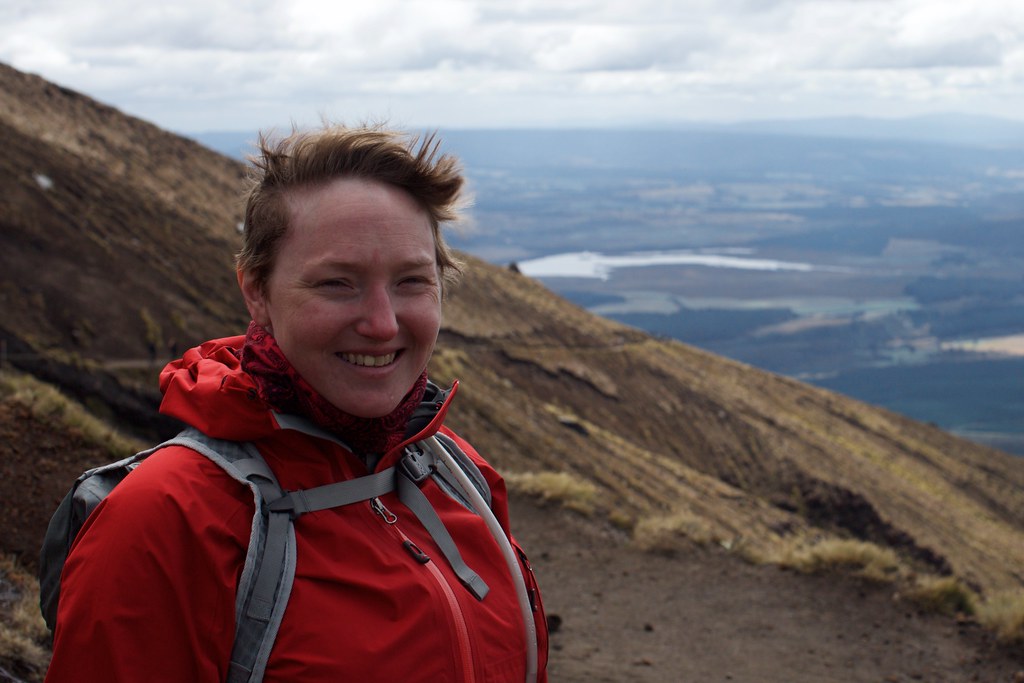

A fellow hiker snapped this nice photo, just before we set out again:

Fortified by the rest, we made good time across the plateau to the north, and then climbed another hill to arrive at the edge of Blue Lake. It was gorgeous; the kind of rugged-looking primeval terrain that an artist might put on the cover of a fantasy novel to grab the reader’s eye.

We took the opportunity to make silly poses in front of it. Kerry’s fantasy novel is called “Space-Queen Of The Freezing Teapots.” Mine is called “I Can’t Believe How Silly Kerry Is.”

I couldn’t help asking myself, why would this terrain be so inspiring? As I walked along I came up with a pretty good theory: It inspires dramatic tension because it’s exposed. Unlike a dense forest or the crowded streets of a city, this terrain is composed only of things that are gigantic – the lake, the ridge, the sky – and things that are tiny. Anything medium-sized that you construct in it, or send wandering through it, can only look fragile and insignificant by comparison. … Or it will be so far away that you won’t see it at all.

So either you’re lost, or you’re totally exposed and vulnerable. Quite a setting for drama! There isn’t even a single bush growing around the shore of the lake that you could hide behind. About the only way you could surprise someone would be to bury yourself in rocks and wait until they wander past you on the trail. (I bet some treacherous bandits in Mongolia have done just that!)

Eventually we passed around the side of a hill, losing sight of Blue Lake, and discovered one good hiding place:

… So we took another pee break and ate snacks there. The wind was not as bitterly cold as before, but still cold.

Eventually we passed around to the north face of the Tongariro complex. From this point the trail only went downward. It felt like we were more than two thirds done with the crossing, but for the sheer distance we had to walk, it was closer to halfway.

We were treated to another lovely panorama, this one quite different from the last. We could see Lake Taupo in the far distance.

The track below looked easy enough to walk, and we thought we were right on schedule to make it to the shuttle stop at the end by 5:00pm. We didn’t reckon that most of the remaining path was hidden in the forest beyond.

Along the way we saw some more geothermal activity, and a sign sternly warning us to keep our distance.

After an eternity of foot-numbing descent, we arrived at the Ketetahi cabin, a structure that used to offer overnight stays and cooking equipment to hikers before it was damaged in the 2012 volcanic eruption.

In 2012 an explosion shot thousands of rocks high into the air, and one of them came down right through the roof of the cabin and smashed one of the bunk beds. Thankfully, it was not occupied at the time!

Now the cabin is only good for temporary shelter and bathroom breaks, while the forestry service decides what to do with it. The current proposition is fix up the cabin but seal off the damaged room – including a plastic plate over the hole – and turn it into an exhibit showing the power and unpredictability of the volcano.

We got a good look at the bas-relief map on the table and saw that yes, now we were more than 2/3 of the way. Sheesh!

We walked as fast as we could, very conscious of the time. The trail finally leveled out and the forest closed around us. Soon we passed this sign:

So what in the world is a “lahar”?

The USGS website has an answer: It’s an “Indonesian term that describes a hot or cold mixture of water and rock fragments flowing down the slopes of a volcano and (or) river valleys.”

Basically a flash-flood of cement that comes roaring down out of the mountains without warning and half-drowns, half-bulldozes everything in its way. Terrifying!

At this point we were almost jogging, trying to make the 5:00pm pickup. For the last half-hour we did jog, when our sore feet would allow us to. I still paused to snap a few pictures of the amazing foliage around us — I couldn’t help it!

Whoah. I don't think I've ever seen such a huge specimen of this type of lichen anywhere before... ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudevernia_furfuracea )

The shuttle driver waited a few minutes after we arrived, since there was one more group behind us on the trail that hadn’t appeared yet. If we’d known that the driver would wait past pickup time, we wouldn’t have taxed ourselves so much on the last few miles. Oh well.

Back at the hotel we exploded our luggage and took the longest showers ever. Then we rode to the restaurant for a huge dinner:

We checked the weather for tomorrow, and the transportation out of National Park, and decided to do one last day of cross-country riding, all downhill to Taumurunui!