Lost In The Woods

This trip was too much to handle. I went about 47 miles and burned almost 2400 calories according to the Mac, and had to call Pit Crew La and ask for a pickup between Felton and Ben Lomond, almost ten miles away from my goal of Santa Cruz. I took some downright stupid risks and made some inexcusable mistakes… And I clearly haven’t learned my lesson, because if I’d known I would get out of it alive, I would have done it anyway.

I left from Cupertino at around 3:00pm last Sunday, fortified with 10 hours of sleep and a huge meal in me from the night before. I still didn’t have the advanced battery pack built for my bicycle, but I was tired of waiting for the parts to arrive and didn’t want it to stop me from riding.

- The Risk: Leaving late in the day can make you rush to meet your deadlines. Rushing on a bike ride is bad.

- The Solution: Leave earlier, duh.

I pedaled north from Apple in high spirits, then turned left on Homestead Road, with only light traffic. The city biking was uneventful until I passed down a side street and saw this sign:

Even in this high-rent district, “the kids” still get away with something. I laughed out loud and nearly swerved into a ditch.

I passed into a suburban area and began to encounter a lot of bicyclists. Almost all of them were men. Almost all of them were wearing custom biking clothes, most of them with racing decals. Everyone had that lean, gazelle-like shape, like they’d been doing this forever. There were absolutely no pedestrians. The few people I did see on foot were walking in or out of restaurants. The contrast with the diversity of downtown San Jose, ten miles east, was telling.

I could tell it was an affluent part of town because no one was smiling, and no one said hello; not even the fellow bicyclists. But once I got further up into the hills, the cyclists reduced to the handful who were traveling the same route, and they were very friendly. We would always nod and smile, and occasionally chat as we passed or re-passed each other. Since we were on this road, we were obviously sharing the same adventure.

It got quiet, so I switched to the ambient playlist. I passed a stables and a pasture, and saw a deer resting beneath a tree, and a rabbit darting around by the side of the road. Small lizards went zipping under rocks as I approached. Vineyards and orchards went rolling by. The houses grew more palatial, some almost crossing into parody, with roman columns, crosshatched colonial shutters and brickwork, iron-filigree windows, and stone cherubs spewing water into fountains. Nice stuff, but mostly it made me think, “If the poor migrant workers in downtown San Jose saw this, they would be enormously aggravated at this community.” … And about ten miles’ distance through thin air is the only wall separating these groups.

Honestly though, I’m not as angry with “the rich” as a group as I was when I was younger. I’ve come to understand that they are about as morally diverse as any other slice of people, except they tend to be much more strongly imprisoned by genetics. When you live with – or even owe your survival to – genetically inherited wealth, you are compelled to believe that the genes demarcating your family line actually contain some justification for the inheritance. This belief can easily poison you and your relationship with most of the world. Be that as it may, the desire to spend money on your kids, and your kids only, is part of us all… So, whatchagonnado.

Anyway, I took frequent rest stops and ate grapes from my saddlebag, and chatted on the phone with La. With my quieter music playing I could hear better, so I began to switchback up the increasingly steep roads. The rushing sound of the approaching vehicles gave me plenty of time to get back to the safety of the curb.

- The Risk: Switchbacking up steep hills puts you in danger of collision with the huge metal death monsters otherwise known as “cars”.

- The Solution: Get a decent low gear on your damn bike so you don’t have to switchback.

The iPhone map guided me up past the nature preserve and the various landmarks. In general it was easier to find my way this time because I understood that not every curve in the road is actually on the digital map… The map is a line drawn by interpolating between points, and there aren’t enough points to describe all the curves, so you only get an approximation of what the road does.

- The Risk: When you rely on a digital map, what you see is not always what you get, and it’s hard to track your exact location.

- The Solution: Memorize your route, go with a guide, or use a GPS tracker with your map. Or all three.

On a particularly steep rise, the road went around a sharp curve directly into the setting sun. I’d been riding beneath forest canopy for almost an hour, so my sunglasses were in my saddlebag. Instead of stopping immediately to put them on, I tried to switchback my way up around the curve while half-blinded, and was so distracted that I almost rode into the path of a fellow bicyclist who was speeding down the mountain.

- The Risk: Almost all bike accidents happen during sunset hours when the light can blind people, and approaching cyclists do not make noise like cars do, so you can’t rely on your hearing.

- The Solution: Wear sunglasses and keep them on until the sun has set, so you don’t get blinded by surprise coming around a curve and fling yourself over a railing.

I stopped at the edge of a preserve to drink water and futz around with the camera. The second I stepped off the bike I was surrounded by a cloud of mosquitoes and flies. “Ahh yes, the sunset hours,” I muttered. I laid my bike by the roadside and went marching up into the hills for a while. Almost caught a bunny rabbit on film, but he was too wascally. While setting up a picture of some sunlit grass, I suddenly observed that my arms were almost red with sun exposure.

- The Risk: Short sleeves in the summer will get you fried by the sun and then eaten alive by insects.

- The Solution: If you’re a “touring” rider, consider a long-sleeved white or reflective garment. Perhaps not those tiny spandex things the pros wear, since a determined mosquito can poke right through those, but something with at least a little thickness to it.

Back in the saddle I pedaled hard for a while to distance myself from the insect cloud. Only a couple of determined flies kept pace. I don’t know what they were after … I can’t imagine them being able to drink anything off me that makes up for the energy they expend chasing me down. Oh wait, there’s an easy explanation for this: Flies are dumb.

I passed a gang of llamas parading around some very pretty farmland. The slope leveled off, informing me that I was at the top of the mountain and due to encounter Skyline Boulevard soon. The setting sun continued to blind me around many of the curves. Finally I came to the four-way intersection I was looking for, where Page Mill Road crosses Skyline Boulevard and turns into Alpine Road. About a mile further I stopped to eat the burrito that Pit Crew La made for me. Looking west, I could see the fingers of mist filling the valleys between me and the coast. None of that moisture makes it to San Jose. Dammit.

It was nice and quiet so I decided to walk to the edge of the road and pee. My bike shorts have no front zipper, so I have to pull them partway down, which is quite awkward. “Of course,” I thought, “the second I get them down, a car’s going to come rushing around the corner. So I might as well get this over with… Yep. There’s the car, right on cue…”

I yanked my shorts back up and pretended to be arranging luggage on the bike. The car went out of sight, so I got ready to pee again, but of course a second car came up. “Oh yeah. Cars usually appear in groups,” I thought. Then I got ready to pee a third time… And a third car zoomed by, going the other way. A minivan with a bunch of kids pressed to the windows. “Fine,” I shouted. “I don’t care who sees me. I am peeing on the side of the road right now.”

…And since I was already exasperated, no cars appeared. I put my headphones back up, put my helmet back on, remounted the bike, and kept riding west.

Gradually the road squiggled around to the south, and then became extremely steep. Toast-your-brake-pads steep. Around a couple of curves I had to brake so hard my front wheel began making a terrific squealing noise. I should really adjust that, I guess, but it’s already come in handy a few times to alert drivers to my presence.

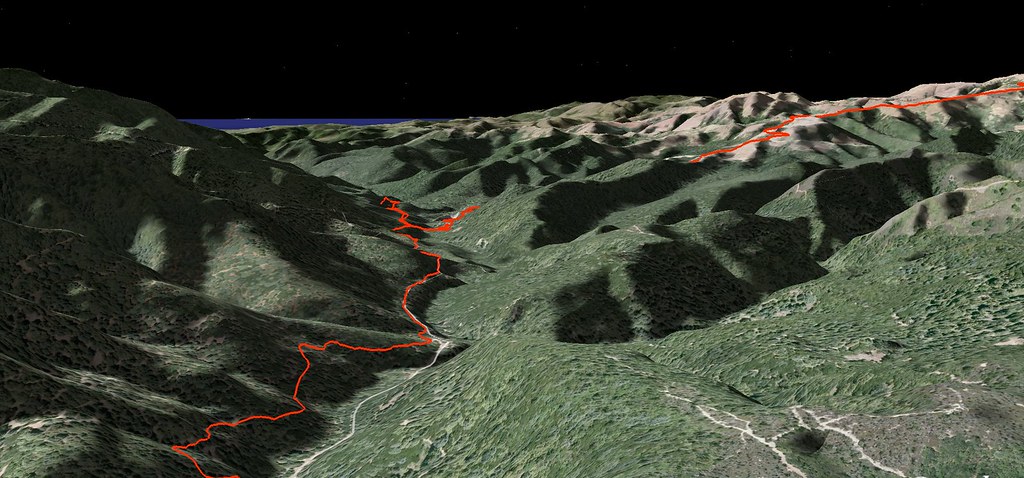

I shot out from behind a hill and all of a sudden I was staring down the mountainside, across a valley, and out over the ocean. Except that instead of water, I was seeing a dense ocean of clouds. The whole coastline was covered in a thick wooly blanket, starting at the base of the hills and extending all the way past the horizon. The rapidly setting sun lit the tops of the cloudscape, and drew a line of fire all along the outer rim. As I rushed down the peak of the hill towards this scene, I looked down into the valley on my right, filled with eerie dusk shadows and cool air. It seemed to go by in seconds, and as it curved up to meet the hillside, another valley opened on my left, filled with more huge shadows and rushing air. I glanced at my GPS display and observed through streaming eyes that I was going almost 40 miles per hour.

Totally worth the trip.

After gazing slack-jawed at the terrain for a while I realized I should stop and take a few pictures. The sunlight got very dim so I turned on my bike lamp. About half a mile later the road did another nose-dive and entered a forest. A sign blew past me, and 200 yards after that I finally parsed what I had read: “Not a through street.”

“Well that doesn’t make sense,” I thought. “According to the map I examined last night, this road goes down to a nature preserve and campground, then connects with Highway 9 and leads to Boulder Creek…” I’d seen the signs for the nature preserve, so I assumed I was still on the right track, but… “Not a through street?”

- The Risk: You’ve checked the route on several maps, but real-world conditions vary, and your plans are destroyed.

- The Solution: Come prepared to encounter harsher conditions than the map says. Bring enough gear to stay out longer than you plan.

“Maybe it’s passable by bike, but not cars,” I told myself. I’d already gone way, way down the hill, so I was trying to rationalize going forward instead of turning around and inching my way back up. “Let’s just get down there and look around…”

The road arrived at an open checkpoint, like the kind you see in front of nature preserves. I slowed down long enough to see that there was no one in the booth, then kept going. The forest canopy got very high and blocked out the remains of the sun. Abruptly it was night. I glanced at the iPhone and it said 8:00.

The road became wide and smooth as it snaked between the trees. After riding in soft silence for a while, I began to hear distant voices, and saw the yellow windows of lodge houses. The road split, then split again. I tried to determine if I was still heading south by craning my neck to catch the moon flickering in the branches, but all I saw was blackness. It felt like south. Short gravel driveways appeared on either side of the road, and I realized I was passing unoccupied campsites. Was there another way out of this place? I had definitely seen one on the map at home…

I saw a sign ahead, pointing down a thinner road that branched off and up a hill. “Old Haul Road”. That sounded encouraging. A road good for hauling stuff is a road that goes somewhere. It became so steep that I had to dismount and push my bike, but only for a minute. At the top of the hill was another sign: “BRIDGE OUT.”

Well that explains it. No bridge, no escape for cars. I stopped to catch my breath and consider my situation. It was 8:30pm on a Sunday night. I was on a bike, at the bottom of an enormous hill, 35 miles from home. I had probably deviated from my route, which had obviously been inaccurate to begin with. My phone, my traveling lifeline, was displaying the words “No Service”.

Well, if I was going to bike all the way back up that hill, I would definitely be late to Santa Cruz. So I’d need to find a payphone at one of the lodge buildings and call up The La. That would be the smart thing to do. But on the other hand, what if the bridge is only closed for cars? Maybe I can just bike right across it anyway.

I decided to go have a look. How big of a bridge can it be, anyway, here in a campground at the bottom of a valley?

The road twisted and turned through thick forest, then opened up to a large dirt clearing. A small, temporary-looking building stood in the middle of it, next to a stack of wood and a huge mound of debris. Some construction equipment lay scattered around, bluish-grey and shadowy in the weak moonlight. At the opposite end of the clearing I saw a few wooden sawhorses with red plastic ribbon strung between them, and a large metal sign propped in front. I rode up to the sign and read it with my bike light: “BRIDGE OUT. Road closed to cars, bicycles, pedestrians. DO NOT ENTER.” Et cetera.

Just beyond the ribbon, the construction workers had pushed together a thick pile of branches and rocks, physically blocking the road. But beyond that I could see the road continued. So I wheeled my bike around the blockade and kept going. After another 30 yards, the asphalt of the road connected to a grey strip of concrete about a foot thick, like the lip of a bridge, but without the bridge. Beyond it was darkness and the faint trickle of flowing water.

I leaned my bike against a concrete barrier nearby, and detached my iPhone from the holder. I set the iPhone to the “adjust brightness” screen, which is mostly a big white rectangle, and turned the brightness all the way up. It made a pretty good flashlight. Over the edge of the concrete lip I could see the worn dirt slope of a riverbank, and beyond that a shallow creek. I climbed carefully down and scanned the area for an easy place to cross, holding the iPhone out in front of me like some enchanted weapon from Clash Of The Titans. On my right, downstream, the huge broken slabs of the bridge lay buried in the mud. To my left, some flat rocks formed an easy path over the water. I stepped across them and then climbed carefully up the hill, where I found the torn edge of the road. It clearly continued beyond the missing bridge. The way was open.

So, I climbed back over to the other side, grabbed my bike, and carried it across, holding the iPhone in my teeth to light the way. Back in the saddle on the far side of the creek, I began pedaling, and my bike light pulsed into life. The scene it revealed made me very worried: The road was littered with branches and redwood leaves so profusely that it looked like the forest might swallow it up. Did I just haul my bike over here for nothing?

Nervously I rode around the corner, snapping twigs and branches. The road continued up a hill. Partway up it, I saw a large gravel-covered clearing on my left with a couple of small buildings dimly visible. I pedaled up to them and observed they were covered with vines redwood leaves. The windows were dirty. The front door of the smaller building was obscured by a blackened weed that had burst from the cement landing and then dried out. I got the impression I was looking at a checkpoint, like the one at the campground entrance. This road had obviously been closed for years.

“Spooky stuff!”, I whispered to myself, and rode out of the clearing. The hill got steep so I began walking the bike. Only a quarter-mile up, the road connected to a wider dirt-and-gravel road that appeared to be in better condition. That was surprising. Nearby I spotted a wooden frame with a map posted on it, under a pane of thick plastic. In the lower left corner was an X, labeled “YOU ARE HERE”. The X was positioned in the vague middle of a hairy mass of lines, all connecting at right angles to a thicker, straight line that ran diagonally down the map from left to right. That line was apparently Old Haul Road. Since I’d joined this road from the trunk of a T-intersection, I had previously been on some other road. Where the hell had I been?

I looked around the X for roads that passed over a river, and found several. The curve that fit the route best was a road that joined up from the south. So if I had been on that road, and I wanted to head southeast on Long Haul Road towards Santa Cruz, I should turn right.

I turned and began pedaling. The road was in good shape, and refreshingly straight. Pleased to be making easy progress, I let my mind wander. Fifteen minutes went by. Then I arrived at another T-junction, with a sign posted. Old Haul Road to the left, Pescadero Creek to the right. With the distance I’d just gone, I was probably off the edge of the map back at the kiosk, so even if I could remember any details from that map, or had taken a picture, it wouldn’t have helped. I decided to turn right since it was probably more towards the coast, and pedaled on for about a hundred yards, then drifted to a stop.

My iPhone had no signal, but I still had my GPS tracker. I’d just remembered that it could show a miniature drawing of where I’d gone. It had no roads or detail, but by looking at the shape of my route, I could orient myself and figure out which road I should really be taking. I turned on the eerie green backlight and poked at the device for a couple of minutes, confused by the awkward menu system, and finally got the line to appear. There was my route, very clearly going… Northwest. Oops.

This was Old Haul Road alright. I could tell because the line on the display matched the shape of the line back at the kiosk. But I’d just cycled almost two miles in the wrong direction on it.

I stood there swearing for a while, then congratulated myself for finally remembering that my GPS tracker could do that, then wheeled the bike around and rode back the way I came. 15 minutes later I blew by the kiosk. The road continued for another five minutes, then was interrupted by a very serious looking gate in front of a bridge. A metal sign posted above the gate declared that the land across the bridge was owned by a logging company, and that no cars, horses, or bicycles were allowed, and no pedestrians after dark.

Time to break some laws. I monkeyed the bike around the gate and walked it across the bridge, then got back on and kept pedaling.

The gravel crunched under my tires. Occasionally it would become thick and moor the bike, throwing me off balance and forcing me to walk. I passed a lot of intersecting roads, but I had convinced myself that all of these were for logging access and didn’t go anywhere, so I stayed on “Old Haul Road” wherever the road signs indicated. The GPS console said I was going in a direction that matched the road I’d seen on the map at home, which was a good sign, but I was constantly worried that the road would simply end.

I got a serious fright when I rode onto a straight section and saw a tractor and a backhoe in the distance, parked in the middle of the road, next to a pile of dirt. “Oh CRAP,” I thought to myself. “Don’t tell me they’re still building the road. After all this, am I going to have to turn around?”

I approached the pile of dirt to see if there was even a trail on the other side. When I got there I found that the road kept going, just as straight and wide as before. For some reason there was just a big pile of dirt heaped in the middle of it. Uh, okay…

So I rode on. Four or five miles later the road brought me through a large clearing, dotted with young fir trees that leaned and stretched eerily in the moonlight. I felt a surge of instinctive paranormal fear, and had to stop and calm myself down. “If you start seeing ghosts behind every tree,” I told myself, “you’re going to have a really hard time out here.” I checked the iPhone clock and it said 10:30. I was due in Santa Cruz in half an hour, and I had absolutely no idea how far I needed to go. After a few deep breaths my nerves settled down enough to keep riding.

More crunching gravel, more steep hills and intersections. A few of them were unlabeled so I just looked at my GPS map and picked the one that went southeast. Every now and then I’d hear the noise of some unknown animal crashing around in the bushes. Once I heard it so close by that I turned around and made a very loud hissing sound at it. It’s the sound I always make at forest animals. It scares the crap out of them but doesn’t sound human, so I don’t reveal my presence to other humans when I make it, which for some reason has always been important to me when walking around in the woods. (Probably because a lot of the time when I was growing up, going into the woods meant trespassing on other people’s property.)

I came to another clearing. This one had been bulldozed flat and laid with gravel, making a staging area. A decrepit-looking tanker truck was parked on the left edge. Ahead of me on the right I could see a wooden fence with a camping trailer installed next to it on cement blocks. Beyond an opening in the fence I saw more trailers, arranged on either side of a narrow driveway. Beyond that, a bright electric light illuminated part of a low building. This looked like the outpost of some construction or logging business.

Aside from the driveway, there was another road leading out of the clearing to my left. I didn’t want to go blundering up to the trailers and wake the sleeping humans within… I would have rather turned around than do that… But luckily I didn’t have to make that choice. I took the road leading left. No sooner had I gone 100 yards around a corner when a dog began to bark. Not the high, alert bark of a family dog, but the low, explosive, coughing bark of a large muscular guard dog. A tone that said to the base of my brain: “If I find you, I will bite your throat right off your body.”

A few weeks ago I’d been walking around outside my house, bringing some food to a stray cat, when I heard dogs barking and a woman screaming in panic. I went striding towards the sound and saw a young man holding the collar of an enormous pit bull. The dog was panting heavily from it’s wide flat mouth and seemed to be in a good mood, but was pulling to be free of the boy, who was having serious trouble keeping the dog in place.

“Is this your dog?” I asked him. “No,” he replied. We talked, and I learned that the boy’s mother had been out walking her two small dogs when this dog had simply wandered up and started fighting with them. The mother’s screaming had brought out the son, who held the dog back while she fled into the house. Now he was standing outside in his boxer shorts at 10pm trying to restrain an anonymous dog that weighed only a few pounds less than he did.

We took turns holding his collar, which was actually a thick loop of rope with a broken tassel hanging off of it, and The La (who had walked up behind me) called the police and then an Animal Control unit to come deal with the beast. Meanwhile, we were lucky that the dog had some instinctive respect for humans packed away in its brain, because as I spoke with it and groomed it (while practically sitting on it to keep it in place), it calmed down a little bit and remained in a good mood. At the time I wondered if it was just happy to be free. It had clearly gnawed through it’s rope leash some time ago.

The cops arrived and they handed me a strong skinny leash, and asked me to clip it to the dog since I seemed to be keeping him calm. It took several of us to corral the reluctant animal but we eventually tethered him to a metal signpost. Once he was attached to an object he stopped jumping around. We all chatted with the police for a while, who expressed their frustration with pit-bull owners and owners of large meaty breeds in general. “What ever happened to the Golden Retriever?” I asked. “You know, dogs with actual brains?” “Yeah, seriously,” one of them said. The kid went back into his house with his mother. I petted the dog one last time and then left him for Animal Control.

Anyway, that incident was fresh in my mind while I stood on the road in the middle of the forest. Big dogs with big mouths, in bad moods, were very scary. And this time I was alone, and clearly trespassing. There was no way I could make a case for “I was just riding and got lost, sir.” Not after 15 miles.

The huge booming bark continued for several minutes. It echoed across the valley and back, and I realized that the dog was probably barking at it’s own echo, since I’d long stopped making noise. Finally it trailed off, but when I resumed riding, the dog resumed barking less than 50 yards later. With a sinking feeling in my gut I realized that the road was leading me directly towards the sound.

Like an idiot, being an idiot for the fifth or sixth time that day, I rode on. In another 50 yards I saw a driveway on my left, and the reverberation of the barking changed, informing me that I had just passed within direct line of sight with the dog. As soon as I did so, the barking ceased. That was even more unnerving, because most dogs quit barking when they’re running. Was I about to be jumped by a guard dog?

I pedaled as hard as I could up the hill, for almost 200 yards, expecting at any moment to hear barking just a few feet away, or the bite of teeth in my leg. I’d been bitten by dogs just twice in my life, and both times they were just ordinary neighborhood dogs. I was anticipating far worse from this one.

But the attack never came. I rolled to a stop, panting, and tried to hear the presence of any other animal. None. What had happened? After standing in place for a few minutes to catch my breath, I figured it out: The bike lamp. It’s almost as bright as the headlight of a motorcycle. The dog had seen my lamp, which obscured everything else, and had come to the conclusion that I was a vehicle, and that there was no point in barking.

- The Risk: A guy on a bike looks like a giant hamhock to nearby dogs.

- The Solution: Blind them with science.

Twenty feet further up the hill was a sign nailed to a 2×4, facing the other direction. I rode over to it and read the writing on the front: “No Trespassing.” That was a relief. I was riding out of a place that required that sign. Just ahead I found the paved ribbon of an actual public road. Hot damn! Back in civilization. I turned on the iPhone and it showed a few bars of signal.

The first thing I did was call La, to tell her I would probably be later than 11:00pm. But she was busy driving over Highway 17, so I said I’d call back. Then I went looking for a street sign, and found none. So I turned east on the road and began pedaling. It switched back a few times, then began to climb straight up the hill. Was this taking me back up the mountain? That would suck.

I rode for a while longer, unsure what to do, and then got a bright idea. I’d compare the squiggle on my GPS route with the shapes of the roads near Boulder Creek. Maybe I’d find a match. In only a few minutes I had it: I was on Saw Mill Road. That intersected Highway 236, and Highway 9, in less than a mile. Eagerly I rode on, zig-zagging up the steep road and chatting with The La over my headset. I told her I’d be late, and she said she could do some shopping, so it wouldn’t be a big deal.

I hung up the phone after I was on Highway 9, and fired up the music player since I was no longer worried about battery life. By the time I passed through Ben Lomond I was feeling pretty run-down, because the cold air was turning my arms numb and, like an idiot, I’d forgotten to bring a sweater. I stopped to call The La again and looked at the GPS readout, which said “42.42 miles”. An auspicious number!

We agreed to meet along Highway 9, between Ben Lomond and Felton. She began driving up from Santa Cruz, and we found each other on my 46th mile. Gratefully I loaded myself into the passenger seat, and we drove to Santa Cruz for Saturn Burgers and shakes with our friend Alison.

Quite an adventure. And clearly I have a lot to learn about trip preparedness.