How my bike was stolen, and how I got it back (in spite of myself)

Anyone who knows me, knows how much I love my bicycle Valoria. We’ve had some great adventures, most recently on a trip around Iceland.

When I returned from that I dropped right into my work routine, riding from my sublet in Oakland to the office in Berkeley. The sublet had a back yard, with a very tall fence on all sides and a locked gate, and after being in crime-free Iceland, my guard was down. I stored Valoria and another Giro 20 recumbent in the back yard, underneath a tarp weighted by rocks, because I lived on the second floor and it was really convenient to have her at ground-level each morning.

The theft

Both bicycles were stolen over the Thanksgiving holidays. There was a major rainstorm one night, and the thief used that as cover. Either he scaled the fence – a dicey proposition given how tall it is – or my downstairs neighbors just lost their minds that evening and forgot to close and lock the gate. Regardless, the bikes were gone. And I didn’t find out about it until I got back from vacation, five days later.

I’d been through this before. I cursed myself for being an idiot; for not keeping the bikes locked inside. How could I do that to Valoria? Did the rainstorm blow the tarp aside, revealing the bikes? Was it an inside job and the groundskeepers took them? Was it the roofers I’d seen working on a nearby house, since they could see down into the yard? How could I be so complacent, here in Oakland, where the local homeless population is always on the prowl, specifically for bikes, since they can be chopped and sold or traded to some scumbag for drugs?

(Let’s pause for a second and consider that: There are people here who are so morally bankrupt, they go walking into the homeless camps and trade them fifty bucks of speed for a thousand bucks of stolen property. I reserve judgement in most situations, but in this case … to quote The Young Ones … People like that should be put in little boxes tied up with string, and left in small dark rooms without any electricity.)

Anyway, I knew the routine. I filed a police report. I put an ad on Craigslist. I cased four different flea markets. I walked down into a few homeless camps and asked anyone who looked coherent enough if they had seen my bike, and showed them pictures and offered a reward. Some of the homeless had cellphones and took down my number. I did the legwork, but in my heart I knew it was useless. I hadn’t found Valoria the first time she was stolen.

So I began the process of rebuilding her. I talked with Zach Kaplan, and explained that I was going to build my bike to the exact specs as before. We set up an order, and he said he would keep an eye out in case my bike turned up for sale. Weeks passed. I received the new frame and took it to the powder coater in San Francisco, and took the hub and the rim to a wheel builder. The rebuild was about halfway done.

The ad

Then I left for Los Angeles to visit family. As I was driving up the Grapevine, threading through intense traffic in heavy rain, my phone started ringing. I glanced at it: Zach Kaplan. We’d already dealt with the frame kit, so the only reason he could be calling is if he’d heard something about my stolen bike!

Mind whirling, I pulled over and listened to the message. He’d seen a really suspicious ad on Craigslist, and mailed me the link. I poked at it:

There was my bike. A bunch of parts were stripped off, the stickers had been removed, but it was undeniable. That was MY BIKE.

I swore for an entire minute. I wanted to confront this person immediately. But I was five hours into a six hour drive, and due in Los Angeles that night.

I called Zach and told him yes, it was my bike. We discussed possible ideas. There wasn’t anything I could do from the side of the road, so I completed my drive and spent a near-sleepless night in Los Angeles. Then I threw my full attention at the Craigslist ad.

The thief was combining smart moves with dumb moves. He misspelled recumbent in the title so it wouldn’t appear in searches, but he spelled it correctly in the description, so it got caught by Zach’s filter anyway. He posted the ad in Santa Cruz, 75 miles away from where it was stolen, but the “Bay Area” search range still includes Santa Cruz.

He removed all the stickers – there had been ten of them – and cut off the lock I put around the rack. But the area around the serial number (stamped in the frame behind the front fork) looked untouched in the photo. He removed the mirror, the bags, and the front headlight – including the wiring and the mount for it – but he left the rear taillight in place, which is just as unique of an aftermarket part as the headlight — and the track where the wire had been glued was still clearly visible on the fender.

He posted only one photo, of the bike in front of a garage door. Could be any garage door, in front of any house… But then again, why not take the photo against a blank wall, to be safe?

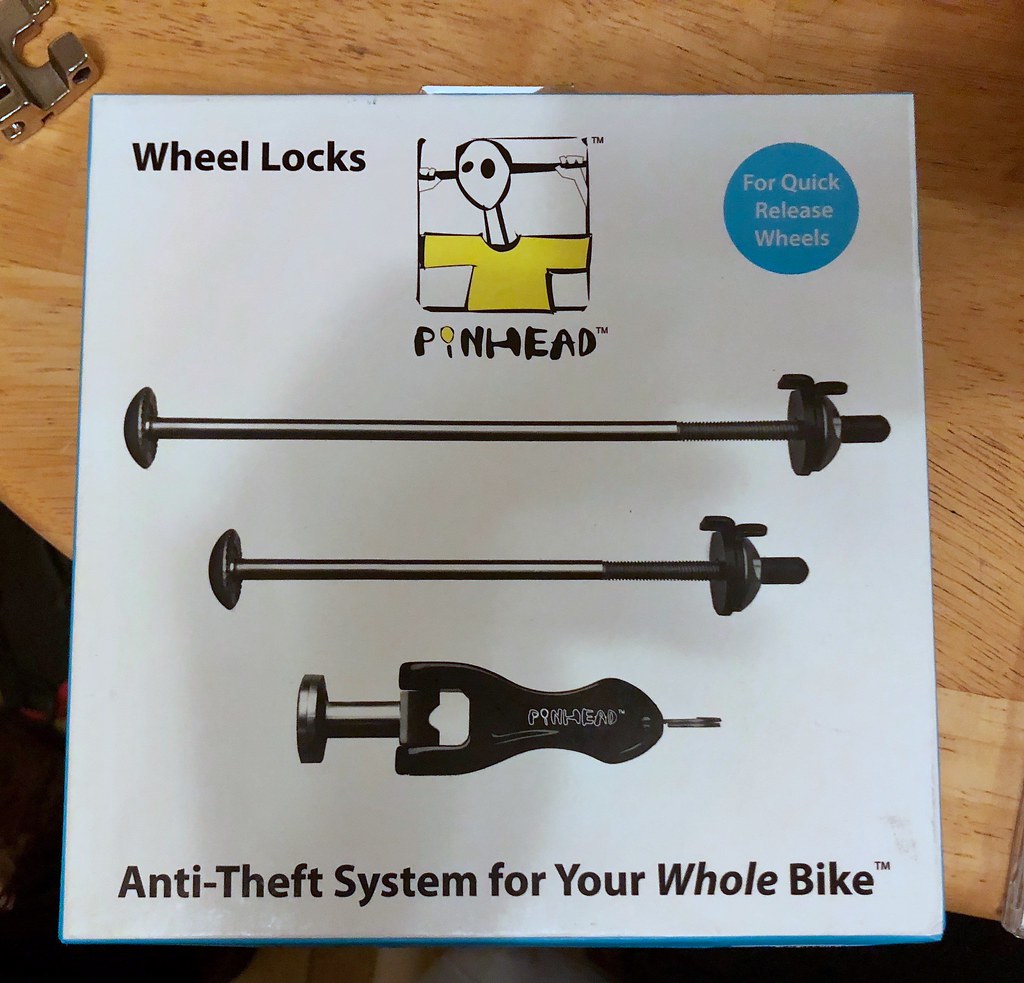

He mentioned the dynamo hub in the ad, but mis-identified it, and failed to mention that the front and rear wheels are locked in place with a pair of steel skewers that can only be removed with a special key. I could see the skewers in the photo.

The key was still hanging on my wall back at the house. I also had the sales receipt with the serial number for the bike, scanned into my paperwork. If I could get near my bike again I could prove beyond all doubt that it was mine.

While I was thinking about that, it occurred to me that the only reason Valoria was still in one piece was probably the lock skewers. A thief would have seen the generator hub in the front wheel immediately, and since wheels are fairly portable, they would have taken that off to sell it, rendering the rest of the bike useless. That’s probably what happened to Valoria the first time I lost her. This time, the lock skewers prevented access to the wheels, and the thief saw that removing them would be very time consuming. So they decided to fence the entire bike. And here it was, on Craigslist.

Okay, what was my first move?

The police

I called the Oakland police and described my situation, including the ad. They said that since the bike was so expensive, stealing it is a felony, and it’s possible to get the FBI involved. The FBI has ways of tracking exchanges on Craigslist. But the usual strategy is to try and set up a meeting with the seller and just convince them to return the property face-to-face. They called it a “civil assist.” An officer would meet with me beforehand, and we would confront the thief together.

I mentioned that the ad was posted in Santa Cruz. They said the jurisdiction was different then, and I needed to work with the Santa Cruz police.

I thanked the Oakland officer and called Santa Cruz. Could they do a “civil assist”? Yes. I was referred to someone who would handle my case. I got a call back, and we took down some details.

Phone tag

Okay, time to send some emails. I emailed the seller, saying I was interested in the bike, and would be back in town soon. I used a new email address, to make sure my name didn’t get dropped in accidentally by some auto-signature function. Our devices are too good at correlating things sometimes.

I also called my friend, Bob Dobbs, and told him to send an interested email as well. The more emails we sent, the more likely we’d drown out other interested parties. Bob cleverly composed a message mentioning that his girlfriend wanted a recumbent too, trying to compel the seller to say that he had my other bike, the Giro 20 that was stolen that night along with Valoria.

Bob got a response about a day later, and had a dialogue with the seller. I told him to schedule the exchange for the day after my drive up to Oakland. Time passed. I fretted that the bike would be sold to someone else, but then I reassured myself that recumbents are much harder to sell than other bikes.

The day of the sale arrived, and Bob hadn’t gotten a response. I called the police in Santa Cruz and told them I might have an exchange set up for today, but I wasn’t sure. The seller had only mentioned that he was on the west side of Santa Cruz. The officer said to pick a public place, like a restaurant, or perhaps the Safeway on Mission street, and propose it with a time, to keep the ball rolling. I told Bob to propose the Safeway at 6:00pm, which he did.

Getting increasingly nervous, I decided I was going to drive down to Santa Cruz, just to be in town in case I needed to talk to an officer in person, or identify the bike, or be part of the exchange, or whatever. I had free time and tomorrow was a day off. If I had to drive down to Santa Cruz tomorrow too, so be it. I’d done that drive plenty of times. I could listen to an audiobook.

I arrived in Santa Cruz about 4:00pm, and asked Bob if he’d gotten a response. Nope. Bob sent another email: “Hey, I’m in Vallejo. If we’re going to meet at six I need to know, so I can get driving.”

Half an hour later he got a response. The seller said, “call me”, and gave a name and a telephone number.

I wrote down the number in my notes, and then called the police dispatch and gave it to them, along with the time and place I’d proposed for a meeting.

Now I had to decide: Do I keep playing email tag with this guy, or call the number? If I called from my phone, he could google my number and get my address, and find out I’m the person he robbed. Maybe Bob could call him? Bob just moved, and his previous address was 170 miles away in Sacramento. If the thief wanted to mess with him he would probably get a Sacramento address and decide it was too far to drive for some pointless revenge.

Bob called him up, and then reported back.

I got some Thai takeout and munched it in the car as I pondered my next move. The safest thing would be to go ahead with the “civil assist” at this guy’s house, and send the officer ahead while I stayed hidden. There was no point in asking my friend to drive down here, if I could pretend to be Bob.

Bob texted the guy to say he was “on his way”. I called dispatch up again, since it was after the shift change.

Suddenly he hung up. I figured that he probably got some information about one of the other things in the stack, maybe something life-and-death. That was alright. There were no lives at stake here.

Crossed wires

I decided to start sending my evidence to the number in the meantime. I gathered together the papers and photos on my laptop, clicked on the number in my notes, and began sending messages. I had the following dialogue:

“That should be a pretty good amount of info,” I said to myself. “It would be pretty hard to claim the bike isn’t mine, with a matching serial number, the lock skewers, AND the powder coat.”

About a minute later I got some more messages from the number, and as I read them I felt confused. Then slowly realization dawned and instead I began to feel mortified, and then panic:

Oh my god. I’d poked the wrong phone number in my notes.

I hadn’t just sent all that identifying information to the police dispatcher. I just sent it directly to the guy who stole my bike.

I had a deer-in-headlights moment. I’d just completely blown my chance at a “civil assist”. How should I deal with this? I tried to walk through it in my head:

This guy just confessed over text that he is in possession of my bike. Either he is going to be a complete moron and taunt me with his criminal act, and I won’t get my bike back, or he is going to try and ransom it for a giant “reward”, or he’s going to be completely honest and just return it to me.

The only way I could have his number is if I got it from Bob. In a moment he’s going to realize what that means: My friend also knows it’s stolen, and has known it the entire time, for days.

He thinks Bob is coming to his house. Why? Not to buy the bike. Perhaps to confront him with the fact that it’s stolen. He might be worried that my friend is intent on violence.

But my friend is not going to show up. Instead, a cop is going to show up. Maybe in an hour, maybe more. This guy has zero incentive to answer the door now.

In the meantime this guy is going to be wondering what he should do. Well, in his situation, what would I do? If I thought I was in danger, I’d probably leave the house. And in that case, the cop would show up, knock on the door, and get nothing.

I needed to respond somehow. If I didn’t respond at all, this guy would definitely assume we mean harm, and things would play out from there. I also needed to somehow explain why I just sent him a huge pile of identifying information that made it trivial for him to track me down.

If I was in cahoots with my friend the whole time, it wouldn’t make sense to send this info. And it wouldn’t make sense to send Bob down to Santa Cruz to “buy” the bike. I’d have to play it like Bob just told me about the ad a few minutes ago, and was acting on his own until then.

Also, if someone’s going to meet this guy before a cop shows up, or before he gets spooked, that someone has to be me. I’m the only one close enough.

I decided I needed to convince him to deal with me, separate from his dialogue with my friend. I also needed some leverage, to motivate him to get this all over with, but just enough that I didn’t spook him if he was actually an honest guy. I was going to play “good cop, bad cop.”

I sat in the car, and ate a few bites of Thai food.

This guy really likes money. I suppose he doesn’t know that I have the option of charging him with felony possession of stolen goods. I could tell him, but he doesn’t have reason to believe me, so it wouldn’t be very good leverage.

As I texted him I drove across town to a bank, and withdrew a fat wad of cash.

He sent me a map marker. Then about three minutes later he shared his location with me on his phone. “I’m at the pub” he said.

The meeting

I wondered if he had friends at the pub, and was going to jump me. Seemed unlikely. His home would be a better place for that. But why was he drawing me away from there all of a sudden? Same deal as me, perhaps: He wants to meet in a public place to avoid potential violence.

On the other hand, perhaps the home is not his employer’s, but his parents’. This guy could be a teenager for all I know, lying about having kids to appear more adult. Selling a used bike in front of his parents would be fine, but if someone showed up demanding return of stolen goods, that might get him in huge trouble.

I decided I didn’t want to be predictable, so I ignored his messages and drove directly to his house. Walked up to it. There was the garage door, just like in the ad. Nice house with a Christmas tree inside. The lights were off. I rang the doorbell and got no answer. Alright, time to scope out the pub.

It was a pretty happening place. Big glass windows and at least fifty people inside; lots of cars in the parking lot. If he was planning to jump me here it would be a really bold move, hardly worth a bike.

I parked a few paces from the door and walked in.

A waitress showed me to a table and I sat down, then texted the guy “I’m here.” Immediately a man turned around at the bar and tapped me on the shoulder. I had been seated less than ten inches from him.

An ordinary guy. Close to my age, similar appearance, not as heavy. He wanted to chat, perhaps to feel out what kind of person I was, but I remained cagey. I hadn’t seen my bike near the pub. I assumed he was going to try and negotiate some kind of ransom, or convince me to follow him somewhere else, and I wasn’t ready to be his friend.

He kept on, talking about bike thieves, and the cycle of theft that’s built up around the homeless camps. I offered a few words to describe my own views, walking a line between enlightened liberal with a fair perspective and do-not-mess-with-me older man from Oakland.

Eventually he reached some kind of conclusion and said “Hey, let’s go get your bike. It’s a few blocks from here in my truck.”

I paused, and said, “Well, here’s where I have to ask for your understanding. I’ve been in some sketchy situations in Oakland, and know people who have been in some way worse situations. Right now the idea of walking with you to some other place to get my bike feels sketchy. But if you were to bring the bike here, with all these people around, I’d feel a lot more comfortable making an exchange.”

I held up my wad of cash to make it clear that there was something in it for him.

He nodded, said he understood completely, and that he would be back. Then he got up and walked out the door.

“Well, he didn’t try and argue me into it. That’s another good sign,” I thought. “Or, I guess he might just be ditching me. If I’m going to be waiting here alone for another hour just to make sure, I might as well order some food…”

I looked over the menu for about ten minutes, and then in the background I saw the man return, and kickstand my bike right outside the front doors of the restaurant. I put down the menu, and walked outside.

“Wow,” I said. “It’s pretty weird seeing this bike again. I was completely convinced it was gone forever. Ripped into pieces like my last bike.”

“Yeah I felt the same when I got my bike back. Found it on Craigslist and the cops impounded it, but then they wouldn’t give it back because I didn’t have enough paperwork. Got into a huge fight with them. Glad you found your bike. And better you have it than me. Recumbents are weird. I do mountain-bike stuff, usually. I tried riding it around but I just couldn’t get used to it. Have you done any long trips?”

“Oh yeah, there was that trip across Colorado…”

We talked about bike touring, which he was excited to try. Then he asked a huge pile of questions about the details of Valoria, especially the generator hub. How was it wired up? How did it perform? Why is the steering so weird? How much gear can I carry? Where does it go? I felt there was no harm in talking to a fellow enthusiast, and perhaps he was looking for some additional verification that the bike was really mine.

The restaurant door swung open. A large crowd was leaving, and the bike was in the way. I dropped a hand on the corner of the handlebars and rolled it aside in one practiced movement. That was probably proof right there: I manipulate this funny-shaped vehicle like a part of my own body.

He asked even more questions. I asked him some questions about who sold him the bike, and where, and when, and got a pretty good description. As we were chatting, my phone rang. I pulled it out and answered it, knowing it was the police dispatch.

My paranoia surged up one more time: If this guy heard me reassuring the cop that everything was fine, he would know he was off the hook with them. Would he suddenly change his attitude, and try to hardball me for the bike?

I got off the phone, and pulled out my wad of cash, and handed it to the man. Despite all my suspicion and paranoia, and bungling attempt at a sting operation, this guy had actually done the right thing, every time. The most he was guilty of was some poor judgement in where he got his bikes. We parted ways with a handshake, and I rolled the Valoria over to my car. Using the key to the lock skewers, I removed the wheels and carefully loaded the frame.

Lessons learned

On the long drive home I asked myself, “What did I learn?”

- Your bike might show up for sale a month after you lose it. Or two or three months.

- Lock skewers can keep your bike whole long enough that you might get it back. They are a bargain.

- It’s pretty hard to tell the difference between someone honestly selling an item they think is legit, and someone trying to fence an item they know is stolen. Legit sellers can be skittish, because they think you might not be a legit buyer.

- A “civil assist” is a nice way to try and recover stolen property, but you need to deal with jurisdiction, and set it up as far in advance as you can.

- Your bike is not safe alone anywhere, unless it is locked to something solid.

- Label any phone number you put in your notes!!

If you could speak, Valoria, what story would you tell?

Someone grabbed you in the middle of the night, and ran you over to some homeless camp for days, maybe tossed you in some bushes below a highway, rusting in the rain.

Then somebody came though selling drugs, and for 50 bucks worth of speed they got a 3000 bike. You were rolled into someone’s truck, taken to some unknown garage or storage unit, then stripped down. Pieces cut from you, markings peeled away, your identity slowly destroyed.

Then, naked, you were tossed indifferently into the back of a box truck and hauled to an open-air market, where some cold weekend morning you were propped up next to your fellow orphaned, kidnapped, bruised hostages, and sold for a fraction of your worth to someone buying you on a whim.

You were ridden awkwardly by a stranger around a random city for weeks, until he finally decided you were a nuisance, and tried to get rid of you — for a little more money, but still a fraction of your worth. Then you were dragged over to a bar for a final transaction, before I had you back.

To get you home I had to take you apart further, and now you lay in pieces, back on my living room floor. If you were a living thing, we would both be crying with exhausted relief, holding each other together.

But you are not a living thing, and the relief I feel is all my own. Not enough for crying, but something real, and inspired from knowing that the story you could tell did not end in scraps at the bottom of a ditch somewhere, but that it will continue — with me, the person who knows you best, the person who made you, and who felt so incomplete and grieved when you were taken.

Tomorrow I will put you back together. I will put every sticker back in place; every bolt and wire. And I will remember that there is no relaxing from the threat of bike thieves. You will never sit somewhere without a lock, inside or outside my house. And even with a lock, I will check on you every day.

And to the man who exploited the homeless, stripped my bike, wasted the time of everyone else in this story, and made money off my pain:

I’ll do whatever I can to put you in jail.