Returning to Reykjavik

July 18, 2021 Filed under Curious

After a long and confusing trip through slumberland where I kept opening doors and walking into different rooms and gardens and basements and tunnels, I opened one more door and found myself awake in the hotel bedroom at 6:00am.

I only knew what time it was from checking my phone, since the light in the windows and the quality of my sleep said nothing. But it was good sleep and I felt ready to start biking again, even at this early hour. In most urban places an early start would be a good idea to avoid the traffic, but there isn’t much traffic anyway even in this most dense part of Iceland, and I would be on bike paths for most of the route.

Despite the huge buffet from yesterday, I was protein starved. I made a note for when I hit the first supermarket: Buy eggs, peanuts, and of course, MORE OF THAT FISH.

Lots of interesting sights, including a statue of Þorsteinn Erlingsson, a poet from the late 1800’s. Generally speaking, I like being in places that have monuments to poets in them. Good priorities!

Yes, I know it would be better for the world if I ate less of that fish… But ever since the last visit, Icelandic fish been sneaking into my daydreams.

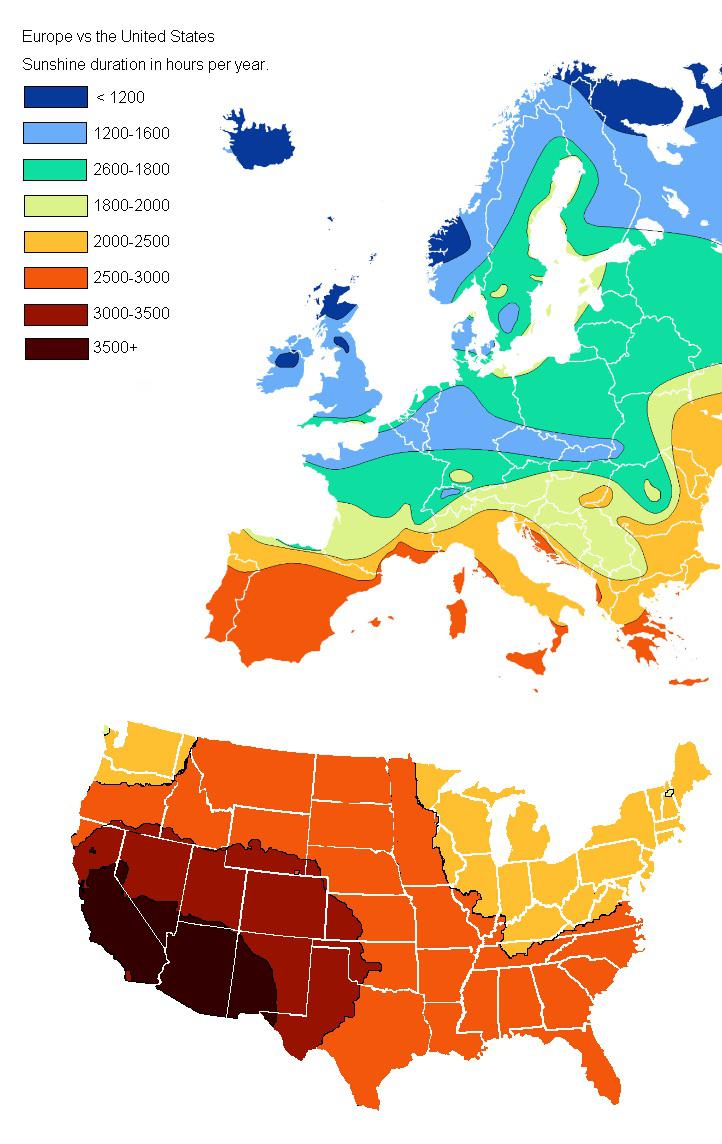

For about seven years of my life I’ve been vegan, in a handful of big intervals, but it’s been many years since the last interval and at this point I don’t know if I could pick it up again. My digestion seemed to work better in the first four decades of my life. But I still think about it, and everything I learned about the impact of fishing and ranching along the way. Iceland is a hard environment for vegans. Almost everything green and tasty needs to be imported from a place that gets more sun.

You’d think that a place with ’round-the-clock sunshine for part of the year would have an excellent growing season. But even though the sun is out for longer during that time, it’s not as bright.

As an aside, I didn’t realize it until I saw that chart, but: There is no place anywhere in Europe that gets as much sun as my home state. Not even close.

I was headed for exactly the same neighborhood I stayed in two years ago, on almost the same route, but I feel like this time I saw a lot more anachronistic viking stuff. I can’t tell how much of this is to impress tourists, and how much is to amuse locals.

Back home, on the border between Oakland and the neighboring city of Berkeley, there are two giant metal sculptures, right next to each other. One is huge metal letters spelling out “HERE”, and the other, on the Oakland side, is huge metal letters spelling out “THERE”. It’s a reference to the activist history of Berkeley and something the author Gertrude Stein said about Oakland, and it was built by a local artist named Steve Gillman. It looks an awful lot like something meant to impress tourists, or make a statement to them, but it’s not. It was commissioned to please the locals.

I think of that, and I wonder: Even if these fake Viking decorations look like they’re here for visitors, even if I think the locals find them abrasive or hilarious, maybe there’s just something going on here that I don’t understand. Maybe this isn’t about me.

Absurd, right?! Whaaaaat!

Well, whether it’s about me (a tourst) or not, I think this stuff is awesome.

Painting the rocks though… I’m honestly a bit confused? I’m going to go ahead and assume that these colors are all non-toxic, because Icelanders.

Some of the art installations look a little less … official … than others!

This piece is pretty cool. It must be really good stainless steel – lots of chromium – to keep from rusting into poop, out in this climate.

My surroundings got urban enough to have a bakery and sandwich bar I could just roll up to, so I chomped a big breakfast.

That kept my stomach busy all the way to the AirBnB. Before I checked in I lounged at an outdoor cafe to eat chocolate, since the weather was good. Outdoor cafes are not common in Iceland for obvious reasons.

I think there’s some politics I’m missing here. Did a group of Russian hackers dig up incriminating stuff about the Iceland government, and earn the appreciation of protesters? I poked around online for context but only found things that would make Icelanders angry at Russian hackers: Stuff about them knocking websites offline, ransoming emails, et cetera.

I shrugged and checked into the AirBnB, which took a while since I had to lock my bike up on the street and haul my bags up several flights of steps.

Keys in foreign lands are always interesting to me. Convergent evolution at work.

I got a tour of the building from the manager, who pointed out the laundry room in the basement, and a back door at ground level that I could use to get the bike off the street.

The room itself was just a bed and four walls. Thankfully the bed was big enough that I could stack some of my gear on it and still sleep.

If this was a more committed AirBnB, they would get rid of some books to free up a shelf or two. It’s probably a more difficult choice in Iceland though, because, where would they go?

There’s only a half-dozen or so used bookstores in the entire country. If you left them on the curb they’d be destroyed before anyone took them. They’d have to go in the trash, which is an unpleasant end for books. Or you’d need to burn them; but Iceland does not have fire pits at campsites, or wood-burning stoves in houses. So… Books accumulate.

Books in Iceland are also an example of the weird, circular nature of a tourism economy. There are plenty of bookstores selling new ones, including books on Icelandic history, guidebooks, and cute books about Vikings and local creatures for kids. All of these were printed elsewhere and shipped in. Tourists will pick them off the shelves, drop them into suitcases, and carry them back out.

…But probably not these books. This collection really looks like stuff that nobody needed.